Testo

Sala LXVI

La Tecnica della pittura antica

La decorazione dipinta negli edifici antichi era eseguita ad affresco: i colori venivano stesi su di uno strato di intonaco ancora umido nel quale, asciugandosi, si incorporavano indelebilmente. Alcuni particolari erano dipinti successivamente, sia a mezzo-fresco, sia a fresco-secco.

Sullo strato di intonaco piu raffinato. l'arriccio, veniva eseguita la "prova" di figurazione ossia la sinopia e il giorno stesso in cui si sarebbe cominciato a dipingere veniva steso il cosi detto intonachino sul quale veniva rapidamente inciso lo schema della decorazione, completo di pressoché tutti i particolari e due o più pittori, cominciando dall'alto, procedevano alla dipintura. Il pictor parietarius, con l'aiuto di lenze, compassi, punteruoli, squadri, simili a quelli esposti nella vetrina, disegnava gli elementi architettonici (colonne, edicole, podi, fastigi) di sfondo e di inquadratura, le linee di contorno degli elementi accessori che sarebbero poi stati definiti con il colore nei minimi particolari.

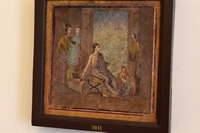

Veniva risparmiato lo spazio per i quadri figurati che il pictor imaginarius poteva eseguire a bottega su una tavola di legno, inserita poi nello spazio appositamente riservato; oppure dipingere direttamente sulla parete dopo la stesura dell'intonachino nella zona del quadro.

Il ritrovamento di impronte o di residui di tavole di legno, o di quadri staccati e poggiati per terra, o "appesi al muro con un rampino di ferro" è la prova che tale tipo di dipinti poteva essere "riportato".

I pittori romani erano copisti, più o meno abili, che riproducevano modelli della grande pittura greca inserendovi a volte varianti di loro creazione. La identica ripetizione di schemi uguali fa pensare all'esistenza e alla circolazione di "cartoni", anche se non siamo in grado di precisare come essi si presentassero per materiale e dimensioni, Per il riporto, I'ingrandimento o il rimpicciolimento dei soggetti si utilizzavano sistemi meccanici come il compasso di proporzione; esistevano maschere e stampini per la riproduzione di motivi decorativi ripetitivi, come le cornici, lesbie o a boccioli di loto. o i "bordi di tappeto".

Non sono noti i nomi di pittori di età romana, con l'eccezione di Fabullus e di Ludius o Studius che decorarono la domus aurea di Nerone, Plinio parla anche di una pittrice, Laia di Cizico, vissuta intorno al 100 a.C., e due quadretti sono una indiretta conferma di ciò in quanto in entrambi e raffigurata una donna che sta dipingendo.

Pitture su marmo

Accanto alia pittura su intonaco e su legno esisteva anche la pittura su marmo, restituita dalle città vesuviane in una decina di esemplari. A lungo quei quadri sono stati considerati monocromi ma analisi fotografiche ai raggi ultravioletti e a fluorescenza UV hanno rivelato la presenza di colori come il rosa, il giallo, il rosso e il nero.

La lastra su cui sono dipinte Ie così dette "Giocatrici di astragali", esposta nella Sala LXVIII, sul retro e assottigliata presso i bordi per essere inserita in una cornice. Di quel quadro conosciamo anche l'autore, Alexandros athenaios che ha firmato" in alto a sinistra. Quasi tutti i dipinti su marmo sono stati trovati a Ercolano sia durante gli scavi settecenteschi, sia negli scavi più recenti. mentre Pompei ne ha restituiti solo due.

The techniques of ancient painting

Painted decoration in ancient buildings was carried out in fresco. The colours were spread on a layer of plaster while it was still wet, and so would become an indelible part of the plaster as it dried. Some details would be painted subsequently on drying or dampened dry plaster, using, respectively the 'mezzo-fresco' or the 'fresco-secco' technique.

A preliminary 'trial' a sketch of the overall composition was carried out on a layer of rough plaster, called the arricio. On the day that the painting was to begin, the so-called intonachino plaster coat was spread. The scheme of the planned decoration was scratched rapidly into this coat, complete in almost all details, and two or more painters would begin the painting itself, storting at the top of the wall.

The pictor parietarius drew the architectural elements (columns, aediculae, bases, pediments) for the background and the frame, employing equipment such as plumb-lines, compasses, punches and set-squares. He also drew the outlines of lesser elements of the composition, elements that were then defined more clearly with colour used for the smallest details.

Space was left for the figured panels that the pictor imaginarius might paint on wooden boards in his studio, to be set into the spaces reserved for them. Otherwise he might paint directly onto the wall in the area reserved for the panel after the scheme had been sketched on the intonachino. The discovery of impressions or remains of wooden boards from panels that were removed or had fallen out of the wall (where they had been fixed by on iron hook) provides evidence that paintings of this kind could be 'brought in'.

Roman painters were copyists of greater or lesser ability, who reproduced originals that were part of a heritage of great Greek painting, adding variations of their own creation from time to time. The identical repetition of the some compositions lead us to believe in the existence and circulation of 'cartoons', even if we can't be sure what form they took, the materials they were made of, or their dimensions. Ancient painters made use of mechanical devices such as proportional dividers to transfer images, and to enlarg or reduce the subjects depicted. Masks and stamps existed for reproducing repeated decorative motifs like cornices, lesbian, lotus buds or 'carpet border' patterns.

We don't know the names of any Roman painters except for Fabullus and Ludius (or Studius) who decorated Nero's Domus Aurea. Pliny also writes of a female painter, Laia of Cyzicus, who lived around 100 BC. Two small panel paintings depicting a woman painting provide indirect confirmation of this phenomenon.

Painting on marble.

Alongside paintings on intonaco and on wood there were also paintings on marble. Ten or so examples of these have been recovered from the Vesuvian cities. For a long time it was thought that these panels were monochrome, but photographic analysis with ultraviolet radiation and UV fluorescence has revealed the existence of colours such as pink, yellow, red and black.

The back of the marble slab on which the so-called Women Playing Knucklebones' is painted (on display in room LXVIII) is bevelled around the edges so it can be set in a cornice. We also know the name of the artist, Alexandros Athenaios (Alexander the Athenian) who 'signed' the piece at the top, on the right. Almost all the paintings on marble were found at Herculaneum, both in 18th century excavations and more recent ones. Only two have been found at Pompeii.

| 11 Gorgone | |

|

|

Il lacunare a schema concentrico con maschera gorgonica, è una delle rare attestazioni della decorazione di un soffitto, parte che veniva ugualmente decorata ad affresco inv. 9973 (da Pompei) |

I colori

I pigmenti usati, come spiega Plinio, erano di origine minerale, vegetale ed animale, come la porpora derivata dalla macerazione di molluschi (myrex brandaris) o come il nero ottenuto con la combustione dell'avorio; in base al loro pregio si distinguevano in piani quelli più diffusi e alla portata comune e in floridi quelli più costosi ma anche più brillanti.

Molto utilizzate erano le ocre dalle quali si traevano innanzi tutto i gialli: la migliore era il sil atticum che si presenta sia in polvere che in grumi, conteneva ferro, silice, alluminio, manganese, magnesio e idrossido di ferro.

I rossi si trovano allo stato naturale di rubrica (ematite) o si otteneva per calcinazione dell'ocra gialla cotta in vasi assolutamente integri perché non si disperdesse il calore. La varietà pregiata del rosso era il cinabro, il minimum degli antichi, (solfuro di mercurio) dalle vivide tonalità brillanti che ben conosciamo nel salone della Villa dei Misteri o nella casa del Vettii, che aveva il difetto di annerire alla luce solare.

Il verde veniva tratto da minerali contenenti glauconite o celadonite, la qualità più pregiata derivava dalla malachite.

Per il bianco si utilizzava il carbonato di calcio una variante particolarmente stabile era il Paretonio, che prendeva nome da una località costiera dell'Egitto e che si trovava anche a Creta e Cirene.

Il blu più diffuso, prodotto inizialmente ad Alessandria, era la così detta "fritta" o blu egizio, derivato da una miscela di sabbia e fior di nitro con rame che veniva grossolanamente limata e bagnata, agglomerata in palline passate in fornace e poi triturate. Le analisi hanno confermato la presenza di cristalli costituiti principalmente da silicati insolubili di rame, ossido di calcio, calcite, quarzo derivanti dalle materie prime impiegate per la sua preparazione. Quando negli ultimi anni della Repubblica C. Vestorius, un uomo d'affari amico di Cicerone, ne introdusse la produzione a Pozzuoli e la diffuse in Campania e in Gallia, fu noto anche con il nome di vestorianum puteolanum. I molto più costosi azzurri naturali erano l'armenium ottenuto dall'azzurrite e lo scythicum ossia il lapislazzuli.

Per il nero si utilizzava per lo più carbonio di origine vegetale, ottenuto dalla combustione di resina, aghi o corteccia di pino o di viticci, ma era diffuso anche quello derivante dalla combustione di ossa

Colours

The pigments employed, as Pliny explains, were mineral vegetal and animal in origin. For example, there was the purple derived from soaking a particular kind of mollusc (myrex brandaris); and the black obtained from burning ivory. Based on their price, they are defined as either 'plain' (the more widespread ones, in common use) or 'florid' (the more expensive, but also more brilliant colours).

Various types of ochre were in widespread use, the source of all shades of yellow. The best was sil atticum, which could be found either as a powder or in lumps, containing iron, silica, aluminium, manganese and iron hydroxide.

Reds could be found in nature as rubrica (haematite) or obtained by calcification of yellow ochre cooked in vessels that were completely sealed so as not to disperse the heat.

The most precious pigment of red was cinnabar (mercury sulphide), called minimum in antiquity. This had the vivid bright tone that we know so well from the reception room of the Villa of the Mysteries and from the House of the Vettii, where, unfortunately, it has blackened through exposure to the sun.

Green could be extracted from minerals containing glauconite or celadonite, the most expensive pigment coming from malachite.

To produce white, Romans used calcium carbonate. A particularly stable version of this was Paretonium, which took its name from a place on the Mediterranean coast of Egypt. It was also found on Crete and Cyrene.

The most widely distributed blue, initially produced at Alexandria, was the so-called 'frit', or 'Egyptian Blue', This was made by mixing and soaking sand, flowers of soda and copper filings. The mixture was formed into pellets and baked in a furnace before being ground up. Analysis has confirmed the presence of crystals primarily made up of insoluble silicates of copper, calcium oxide, calcite and quartz deriving from the primary materials used in the preparation of the pigment. In the last years of the Republic, C. Vestorius, a businessman friend of Cicero, introduced the production of this pigment to Pozzuoli, leading to the spread of its use spread in Campania and Gaul. For this reason it was also known as vestorianum puteolanum. The most expensive natural blue pigments were armenium, obtained from azzurrite, and scythicum, otherwise known as lapislazuli.

To produce black, for the most part Romans used carbon from plant material, by burning pine resin, needles or bark, or vines. However, the use of a black pigment derived from the burning of bone was also widespread.

Strumenti di precisione

Serie 1-2

|

|

serie 3 - 6

|

|

serie 7-10

Serie I - IV

Rimane solo la linea di contorno color seppia nei quadri dipinti su marmo, dopo la perdita dei colori rivelati da analisi fotografiche con raggi ultravioletti.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Foto di Giorgio Manusakis.