Indice dei Musei

presenti in miti3000

Napoli Museo Nazionale - Piano - 1 - Sezione Epigrafi

Testo

MANN - Piano meno uno - Sezione Epigrafi

Sala CL

LA COLONIZZAZIONE GRECA D’OCCIDENTE

Nel corso dell’VIII secolo a.C. nuclei di coloni organizzati si muovono dalla Grecia verso l’occidente per occupare nuovi territori su cui fondare nuove città. La scelta dei siti presuppone una frequentazione precedente delle rotte occidentali, probabilmente per iniziative individuali volte alla ricerca dei metalli o a scopi commerciali. Qualche eco di ciò si coglie nei miti che ambientano in Occidente le gesta di dei ed eroi greci tra i quali, esempio famoso, è l’Odissea.

La colonizzazione greca d’Occidente è un fenomeno composito legato da un lato alle condizioni demografiche, socio-economiche e politiche delle città di partenza, dall’altro alle situazioni che si determinano al momento dell’arrivo.

Il termine greco, apoikia, che designa la colonia, ne sottolinea il distacco dalla madrepatria (metropolis) ma non ne spiega la natura. Le notizie delle fonti letterarie che legano di solito la partenza delle spedizioni coloniali a crisi interne, conseguenza di guerre, carestie o lotte intestine, trova conferma nel modello più diffuso di colonia, quello della città di pianura con ampi territori coltivabili; in qualche caso la scelta del sito è determinata da motivi commerciali o strategici. La colonizzazione greca in Italia introdusse in Magna Grecia e Sicilia la lingua e la cultura greca, importò il modello della polis (città-stato) con la sua organizzazione politica, sociale e territoriale, vi diffuse i culti della madre-patria, favorì la creazione di un artigianato artistico locale a imitazione di quello fiorente in Grecia, diede luogo a proficue forme di contatto con il mondo indigeno e con le realtà preesistenti.

The Western Greek Colonization

In the course of 8th century BC groups of organized colonies moved from Greece westwards to occupy new territories and found new cities. The choice of sites assumes a previous contact of the western sea routes, for individual acting to look for metal or for commercial reasons. An echo of this Greek presence can be seen in the myths and the deeds of gods and Greek heroes of which Odyssey is a well known example.

The Greek colonization is a complex phenomenon due in part to demographic, socio-economic and political conditions, on the other, to the situation colonies found upon their arrival in the new territory. The Greek word for colony apoika marks the separation from mother city (metropolis), but does not specify the nature of this separation.

The indications of literary sources generally linking the departure of colonial expeditions to internal crisis, wars, droughts, internal conflicts seems to find confirmation in the most diffused settlement pattern of the colonial cities-towns in plains with large cultivable land; in some cases, however, the choice of the site is determined by commercial or strategic considerations.

The Greek colonization in Italy introduced the Greek culture in Magna Graecia and in Sicily, adopted the model of polis (city-state) with its political, social and territorial organization, diffused the cults of the mother city, favored the creation of a local artistic crafts based on the imitation of Greek models and developed advantageous contacts with the native world and the preexisting communities.

LE ISTITUZIONI

La frammentarietà delle testimonianze letterarie e della documentazione epigrafica non permette di ricostruire in maniera organica la storia costituzionale delle città italiote. Si possono evidenziare alcuni dati di fatto:

1. Il magistrato eponimo costituisce elemento di datazione nei documenti pubblici e assume nome diverso da città a città (nel decreto di Reggio ad esempio questo ruolo è rivestito dal prytanis, nei decreti di Malta e Agrigento dallo hierothytes; nelle tavole di Eraclea dall’ephoros; altrove dal damiorgòs o dal dèmarchos). Accanto all’eponimo vi sono altri magistrati con specifiche competenze.

2. Come nelle città della madrepatria, vi sono due organi costituzionali, il consiglio e l’assemblea, che discutono e approvano i provvedimenti relativi alla gestione della città. La loro composizione varia nel passaggio dai regimi aristocratici del VI secolo (il consiglio è costituito dagli anziani e l’assemblea è limitata a un numero ristretto di cittadini) ai regimi moderatamente democratici dei secoli successivi in cui tali organi assumono i nomi rispettivamente di bulé e di ekklesia, dèmos o halia

.3. La comunità, come nelle poleis greche, è suddivisa in tribù e in unità minori quali fratrie, demi ecc.. A queste unità minori potrebbero riferirsi le sigle che in molte iscrizioni precedono i nomi dei magistrati o dei cittadini che compiono atti con valore giuridico.

4. Le magistrature cittadine intervengono a tutela della proprietà privata.

5. Uno stretto rapporto intercorre tra città e santuario e la gestione da parte delle autorità politiche dei beni sacri.

The Institutions

Seeing that the literary and epigraphic evidence is extremely fragmentary, it is impossible to reconstruct an organic constitutional history of the Italiot cities. We can point out some common characteristics:

l. The existence of “eponymous” magistrates, a useful element for the dating of public documents. They have different names from city to city (in the decree of Region, for example, it is the prytanis who has this role, in the decrees of Malta and Agrigentum the hierothytes, in the tables of Heraclea the ephoros, elsewhere the damiorgós or dèmarchos). The eponymous magistrate is flanked by other magistrates with specific duties.

2. The presence, as in the Greek cities, of two constitutional organs, the council and the assembly, whose composition changes in the passage from the aristocratic regimes of the 6th century (where the council is composed of the “ancients” and membership of the assembly is restricted to a limited number of citizens) to the moderately democratic regimes of the following centuries, in which these administrative organs assume the name, respectively, of boulè and ekklesia, demos or halía.

3.The community, as in the Greek póleis, is subdivided into tribes and smaller units such as phratries, demoi etc. (to these minor units may refer the acronyms preceding, in many inscriptions, the names of the magistrates or of the citizens who perform acts having judicial value).

4. The role of the town magistrates in the safeguarding of private property (v. the donation tables).

5. A close tie exists between the city and the sanctuary, and the management by the political authorities of sacred goods.

LA DIFFUSIONE DELLA SCRITTURA

Nei territori in cui giunsero i coloni greci introdussero l'uso dell'alfabeto elaborato sul modello di quello fenicio già verso la fine del IX secolo a.C..

Ogni città greca d'Occidente ereditò dalla propria madrepatria le varianti grafiche che distinguevano le scritture locali della Grecia arcaica; l'uniformità dei caratteri fu raggiunta solo alla fine del V secolo a.C..

Le prime attestazioni di scrittura greca in Occidente si riscontrano a Pithecusa (Ischia) dove sono stati rinvenuti testi risalenti alla seconda metà dell'VIII secolo a.C.. Nel resto del mondo greco sono rarissime epigrafi di quell'epoca. Notevole è l'esempio dei tre versi sulla coppa rodia tardo geometrica, nota come “coppa di Nestore” (fig. 1); essi riflettono un colto ambiente conviviale che conosceva l'epos omerico:

«di Nestore, ...la coppa piacevole a bersi.ma chi beve da questa coppa sarà subito

preso dal desiderio di Afrodite dalla bella

corona»

La scrittura delle colonie greche di Occidente influenzò le vicine popolazioni indigene, che, con qualche omissione e qualche aggiunta, usarono i segni dell'alfabeto greco per esprimere la loro lingua. Dall'alfabeto greco derivano la scrittura messapica, quella osca meridionale, in uso presso Brettii, Lucani e Mamertini e, in Sicilia, le scritture dei Siculi, dei Sicani e degli Elimi.

Di vitale importanza storica e culturale fu l'influsso esercitato dall'alfabeto delle colonie euboiche della Campania (Pithecusa, Cuma) nel vicino Lazio, dove diede luogo alla scrittura etrusca e a quella latina, dalla quale derivano le moderne scritture dell'Europa occidentale e il nostro attuale alfabeto.

DIFFUSION OF WRITING

In the new territories where Greek colonies settled, they introduced the alphabet, that was elaborated on the Phoenician model, around the end of the 9th century BC. Each Western Greek city inherited from its mother city specific graphic peculiarities as in Archaic Greece a number of local alphabets coexisted. Greece adopted a uniform character set only at the end of the 5th century BC.

The first evidence of Greek writing in the West comes from Pithekoussai (Ischia), where several texts going back to the second half of the 8th century BC have been found. In the rest of Greek world the epigraphs from this period are extremely rare. A remarkable example are the three verses incised on the Rhodian Late Geometric cup known as “Nestor's Cup” (fig. 1). These verses are composed in a refined convivial milieu, that knew the Homeric epos.

«of Nestor... the cup, pleasant to

drink. But he who drinks from this

cup will at once be seized by the

desire of Aphrodite on the beautiful

crown»

The writing system of the Greeks colonies of the West was picked up by some of the neighbouring indigenous peoples, who adopted the signs of the Greek alphabet, with some additions and omissions, to express their own language. The alphabets of the Messepics, the Southern Oscans (the latter used by the Brettii, the Lucani and the Mamertini) and, in Sicily, of the Siculi, the Sicani and the Elimi, all derive from Greek alphabets. The influx of the Euboean colonies in Campania (Pithekoussai, Cumae) had especially relevant historical and cultural consequences, as it gave rise to the Etruscan and Latin alphabets. From the latter derive the modern writing systems of Western Europe including our own alphabets.

GLI ARTISTI

L’isola di Pithecusa (Ischia) ha restituito la più antica firma di artista finora nota, quella di un vasaio che alla fine dell’VIII secolo a.C. dette una personale interpretazione di forme e decorazioni della ceramica geometrica greca. Su uno dei suoi vasi si legge, tracciata a pittura l’iscrizione ... «inos fece». I numerosi altri vasi firmati rinvenuti in Magna Grecia sono per lo più prodotti attici della seconda metà del VI e degli inizi del V secolo a.C. che furono largamente esportati in Occidente. Nell’ambito di queste produzioni si comincia a distinguere il concetto di plasmare (poieín) da quello del dipingere (grapheín): «il tale fece» oppure «il tale dipinse».

Ci sono giunte numerose firme anche di scultori. Poiché spesso le opere scultoree erano commissionate ad artisti stranieri, questi facevano seguire nella firma, al loro nome anche l’indicazione della loro patria. Ciò ha consentito di individuare, insieme a quanto è tramandato dagli antichi scrittori (Plinio il Vecchio è una fonte importante per questo settore), l’ubicazione delle più antiche scuole di scultura: Argo, Egina, le Cicladi per l’età più antica; Rodi e l’Asia Minore per l’età ellenistica e romana, Atene per tutte le epoche.

A causa della perdita della grande pittura greca, rarissime sono invece le firme di pittori dei più famosi dei quali conosciamo nomi ed opere dalle fonti letterarie. Alle firme dei pittori vanno certamente accostate quelle dei mosaicisti, soprattutto quando queste vengono apposte presso gli emblémata centrali dei mosaici, certamente ricavati da “cartoni” a disegno.

The Artists

The island of Pithekussai (Ischia), has yielded the most ancient artist’s signature known to date, that of a local potter who, at the end of the 8th century BC, gave a personal interpretation of the forms and decoration of Greek Geometric pottery. One of his vases bears the painted inscription ... «Inos made».

The many other signed vases found in Magna Graecia are for the most part the work of Attic potters of the second half of the 6th and the beginning of the 5th century BC, that were widely exported to the West.

These often extremely refined craftsmen began to distinguish the concept of modelling (poieín) from that of painting (graféín), to the point that one can find two signatures on the same vase: «so-and-so made» and «so-and-so painted».

Many sculptors’ signatures have also reached us. Since sculptured works were often ordered to foreign artists, the signature was followed by the indication of their home country. This custom, combined with the information contained in the literary source (especially Pliny the Elder), has enabled scholars to identify the most ancient schools of sculpture: Argos, Aegina, the Cyclades in the early age, Rhodes and Asia Minor in the Hellenistic and Roman ages, Athens in all ages.

As the great Greek painting has been totally lost, signatures of painters are extremely rare. Our knowledge of some of the most famous of them is derived only from the literary sources. Mosaicists also signed their works, sometimes in the central emblémata of the mosaics derived, almost certainly, from drawings on “pattern”.

LA VITA PRIVATA

La scrittura viene utilizzata nelle più elementari manifestazioni della vita privata, ancor prima che in ambito pubblico. I più antichi esempi di iscrizioni, usate per indicare il possesso degli oggetti, sono graffiti su vasi e presentano la formula «io sono del tale», ossia l’oggetto parla in prima persona. Oggetti contrassegnati dal nome del proprietario e da lui utilizzati in vita, lo accompagnano nella sepoltura.

Abbastanza precoce è la consuetudine di apporre sull’oggetto offerto alla divinità un iscrizione che indichi il nome del dedicante, il verbo di dedica e il dio destinatario dell’offerta («il tale dedico [mi dedicò] al dio»). Fra gli oggetti dedicati, dal comune utensile domestico al grande monumento di pietra, vi sono le armi, o parti di armatura, che a volte appartengono al dedicante, ma più spesso sono spoglie tolte al nemico.

Artisti o artigiani offrono alla divinità il prodotto della loro arte. L’iscrizione della piramide fittile offerta dal ceramista Nikomachos, che si presenta sotto forma di appello alla divinità, rivela che la dedica non è solo un atto di devozione ma spesso è fatta per ottenere un contraccambio: in questo caso la fama per l’artista.

Alla sfera privata appartengono infine le iscrizioni funerarie alle quali la pietà dei superstiti affida la memoria del defunto. Nella sua forma primitiva l’iscrizione funeraria è ridotta all’essenziale, come mostra l’esempio di Cuma della fine del VII secolo a.C. in cui è scritto «di Kritobule»; ma successivamente si presenta anche in forme più elaborate. Molto esiguo è il numero delle iscrizioni funerarie anteriori all’epoca romana, rinvenute in Magna Grecia.

Everyday Life

Writing, even before it was employed for public purposes, began to be used for the most down-to-earth necessities of every-day life. Objects were often inscribed with the name of their owner. The most ancient examples are graffiti on vases presenting the formula “I belong to so-and-so”, with the object speaking in the first person.

Objects marked with the name of the owner and used by him during his lifetime are often included among his grave goods. It’s also rather early the custom of inscribing an object offered to a deity with the name of the dedicator, the verb expressing the act of dedicating and the god who receives the offering («the so-and-so offered me to the god»).The dedicated objects are diverse, ranging from domestic utensils to great stone monuments. A special class is represented by weapons or parts of armour, sometimes belonging to the dedicator himself but more often consisting of captured enemy spoils.

Especially interesting are the votive dedications of artists or craftsmen offering the products of their art to the gods. A remarkable example is the fictile pyramid offered by the potter Nicomachos. Its text has the form of an appeal to the deity, revealing that dedications were not just acts of devotion, being often made to obtain some favour in exchange: in this case fame for the artist.

To the private sphere belong funerary inscriptions, to which the piety of the living consigns the memory of the deceased.

In their primitive form, they are reduced to essentials, as is shown by the example from Cumae reproduced here, dated to the end of the 7th century BC, whose inscription simply reads «of Kritoboule» but later on, they also take on more elaborate forms. However the number of funerary inscriptions found in Magna Graecia, before the Romans, are very few.

Considering that funerary inscriptions normally make up about 90% of the surviving epigraphic material, and that Sicily has yielded an extreme variety and abundance of this type of document from the Archaic period on, the scarceness of funerary inscription from Great Greece prior to the Roman age is surprising.

L'Esposizione

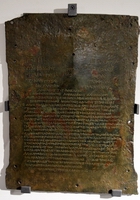

1 Decreto dei Reggini

Bronzo

Fine II - inizi I secolo a.C.

Reggio Calabria

Inv. 112217. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 612

“Sotto la pritania di Nikandros, figlio di Nikodamos, essendo presidente della boulè Sosipolis figlio di Damatrios Chio, nel dodicesimo giorno del mese Hippios, fu deliberato dall’assemblea, come anche dall’assemblea straordinaria e dalla boulè: poiché il pretore dei Romani Gneo Aufidio, figlio di Tito è ben disposto verso la nostra città, mostrandosi degno della sua probità, si incoroni Gneo Aufidio figlio di Tito, pretore dei Romani con una corona di olivo nelle prossime feste in onore di Atena e si nomini, lui e i suoi discendenti, prosseno e benefattore dei Reggini per la benevolenza che ha sempre avuto verso il popolo dei Reggini. La boulè, avendo fatto incidere il decreto su due tavole di bronzo, ne esponga una del bouleuterion e invii l’altra a Gneo Aufidio”.

1 Decree of the Rhegines

Bronze

End of the 2nd - beginning of the 1st century BC.

Reggio Calabria

Inv. 112217. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 612

“Under the prytaneia of Nikandros, son of Nikodamos, while Sosipolis son of Damatrios was president of the boulè, on the twelfth day of the month of Hippios, the following was decreed by the assembly, as well as the extraordinary assembly and the boulè: Since the praetor of the Romans, Gnaeus Aufidius son of Titus, is well disposed towards our city, showing himself worthy of his probity, let Gnaeus Aufidius son of Titus, praetor of the Romans, be crowned with an olive wreath in the upcoming festival in honor of Athena and let him be named, with his descendants, proxenos and benefactor of the Rhegines for the benevolence which he always showed to the Rhegine people. Let the boulè, having had this decree engraved on two bronze tablets, display one in the bouleuterion and send the other to Gnaeus Aufidius”.

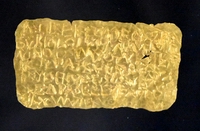

2 Decreto degli Agrigentini

Bronzo

Fine II - inizi I secolo a.C.

Roma, collezione Farnese

Inv. 2487. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 952

Si tratta anche in questo caso di un decreto onorario, emanato dagli Agrigentini ed approvato all’unanimità, in onore del siracusano Demetrio, figlio di Diodoto. Dopo la menzione del magistrato eponimo - lo hierothytes - e delle altre magistrature civiche implicate nell’emanazione del decreto e l’indicazione della data di emissione si enunciano le motivazioni che hanno indotto a concedere all’onorato il titolo di prosseno e benefattore. Si decide infine di incidere il decreto su due lamine di bronzo, l’una da esporre nel bouleuterion, l’altra da consegnare all’onorato.

2 Decree of the Agrigentines

Bronze

End of the 2nd - beginning of the 1st century BC.

Rome, collezione Farnese

Inv. 2487. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 952

This decree was issued in honor of the Syracusan Demetrios, son of Diodotos. After the mention of the eponymous magistrate - the hierothytas - and the other civil magistrates involved in the issuing of the decree, and after the indication of the date of issue, the reasons for granting the titles of proxenos and benefactor to the person being honored are stated. Finally, it is ruled that the decree be incised on two bronze laminae, one to be displayed in the bouleuterion, the other to be given to the honored person.

3 Decreto dei Maltesi

Bronzo

Fine II - inizi I secolo a.C.

Roma, collezione Farnese

Inv. 2488. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 953

Il decreto si apre con un’intitolazione: “Per la prossenia e l’evergesia (concesse) a Demetrio, figlio di Diodoto siracusano e ai suoi discendenti”. Segue la menzione dello hierothytes eponimo e di due arconti e si procede con il consueto formulario. Questa lastra e la precedente, essendo state trovate a Roma, e non nei luoghi di emissione dei decreti, non possono che essere le copie date all’onorato, lo stesso nei due documenti, il quale a Roma, come si evince dal decreto degli Agrigentini, aveva operato a favore delle due città che hanno ufficialmente riconosciuto i suoi meriti.

3 Decree of the Maltese

Bronze

End of the 2nd - beginning of the 1st century BC.

Rome, collezione Farnese

Inv. 2488. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 953

The decree begins with a title: “For (his) proxenia and euergesia (granted) to Demeter, son of Diodotos of Syracuse and his descendants.” This is followed by the mention of the eponymous hierothytes and the two archons, and then by the usual formulation: “It pleased the council and the assembly of the Maltese. Since Demetrios, son of Diodotus of Syracuse, was always benevolent towards our public matters and was often engaged in doing good to each and every citizen, it seems fit that Demetrios, son of Diodotos of Syracuse, be a proxenos and benefactor of the Maltese people, and his descendants as well, for the graciousness and benevolence he always showed to our people. And let this proxenia be inscribed on two bronze tablets, and let one of these be given to Demetrios, son of Diodotos of Syracuse.”

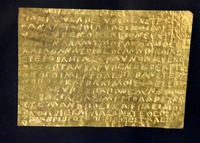

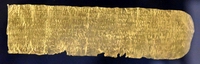

4 Tavole di Eraclea

Bronzo

Fine IV - inizi III secolo a.C.Acinapura, tra Eraclea e Metaponto

Inv. 2480-2481

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 645

Rinvenute nel 1732 nel greto del torrente Salandrella; le due tavole di bronzo recano sulla faccia anteriore due iscrizioni greche databili tra la fine del IV e l’inizio del III secolo a.C.. Sul retro della prima tavola fu inciso nella prima metà del I secolo a.C. un testo legislativo in lingua latina. I testi greci si riferiscono allo stato di abbandono dei terreni sacri di Dioniso (prima tavola) e di Atena polias (seconda tavola), oggetto in parte di occupazioni abusive.

L’assemblea cittadina, convocata in seduta straordinaria (katàkletos alia), tenta di porre rimedio con drastici provvedimenti: il ripristino dei confini mediante la positura di cippi (horoi); la stipula di contratti di affitto con canoni e durata differenziati, a seconda dello stato delle colture, che obbligano l’affittuario ad operare migliorie, a ripristinare e mantenere strade e canali idrici, a non ipotecare i terreni, a presentare garanti per ogni quinquennio. I canoni sono pagati solo in natura. Oltre il nome del magistrato eponimo (l’ephoros come l’omonima magistratura spartana), le tavole menzionano magistrati minori: gli horistai addetti alla positura dei cippi di confine; i polianomoi con funzioni di polizia; i sitagèrtaì, addetti al rifornimento del grano e al suo trasporto nei pubblici magazzini; tecnici chiamati da altre città (il geometras di Napoli). I nomi dei magistrati e dei locatari sono preceduti da sigle di due lettere, relative a suddivisioni del corpo civico, e dall’indicazione di simboli (tripode, scudo, tridente, fiore), forse sigilli familiari. Degni di nota sono il sistema di misurazione delle superfici (le unità sono gyai, schoinoi, oregmata, podes) e la minuziosa descrizione della posizione dei terreni tra vie e canali.

Foto 2- Foto 3- Foto 4- Foto 5

4 Tables of Heraclea

Bronze

End of the 4th beginning of the 3rd century BC.

Acinapura, between Heraclea and Metapontum

Inv. 2480-2481

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 645

The two bronze tables found in 1732, on the bed of the Salandrella creek, in the territory of Heraclea, bear, on their front faces, two Greek inscriptions datable between the end of the 4th and the beginning of the 3rd century BC. On the back part of the first table, an important legislative text in Latin was engraved in the first half of the 1st century BC.

The Greek texts attest the state of ruin and abandon of lands sacred to Dionysus (table I) and Athena Polias (table II), made worse by the illicit occupation of land. The people assembly summed in an extraordinary session (katakletos alia), approved a decree to remedy, by means of these drastic measures: renewing of the boundaries by settings cippi (horoi), on the one hand, stipulating rent contracts with different tariffs and duration according to the state of the cultivated land that obliged the tenants to ensure the restoration and maintenance of canals and roads, not to mortgage the land and to produce guarantors every five years. The rents were only paid in kind.

Besides the name of the eponymous magistrate (viz. the ephor, as in the homonymous Spartan magistrateship), the tables mention minor magistrates, such as the horistái, who supervised the placing of boundary cippi, the polianómoi, with police functions and the sitagertái, in charge of wheat supplies and of its transportation to the public storehouse and finally, technicians summoned from other cities (geometras of Naples).

The names of the magistrates and of the tenants are preceded by two-letter acronyms, probably designating the subdivisions of the citizenship, and by symbols (tripod, shield, trident, flower etc.) apparently corresponding to family seals.

Other interesting elements include the measuring system of surface (the units are gyai, shoinoi, oregmata, podes) and a detailed description of the location of land among roads and canals.

5 Elmo

Bronzo

500-475 a.C.

Locri, probabilmente dal Persephoneion in località Mannella

Inv. 5736. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 631

“Xena [- -] mi dedico a Persefone”.

L’elmo è dedicato a Persefone da Xena [- -]

5 Helmet

Bronze

500-475 BC.

Locri, probably from Persephoneion in Mannella

Inv. 5736. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 631

“Xena [- -] dedicated me to Persephone”.

Helmet dedicated to Persephone by Xena [- -]

6 Piccola ara

Travertino

IV secolo a.C.

Eraclea

Inv. 2479. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 646

“Dorkas dedicò ad Hestia per se stessa e per Atroditia” Il cippo dedicato a Hestia da Dorkas a favore di se stessa e di Aphroditia.

6 Small altar

Travertine

4th century BC.

Heraclea

Inv. 2479. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 646

“Dorkas dedicated to Hestia for herself and for Aphroditia”

Cippus dedicated to Hestia by Dorkas in favour of herself and Aphroditia.

7 Cippo quadrangolare

Tufo

Inizio V secolo a.C.

Locri, Abadessa

Inv. 2482. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 630

Il cippo conserva sulla superficie superiore tracce di un ex-voto. Si tratta dunque di un oggetto votivo, come è confermato nell’iscrizione in dialetto dorico e in alfabeto locrese “Oiniadas e Eukelados e Cheimaros dedicarono alla dea”. La dea destinataria della dedica è Persefone, come indica il luogo di rinvenimento, facente parte del santuario di questa divinità.

7 Quadrangular cippus

Tuff

Beginning of the 5th century BC.

Locri, Abadessa

Inv. 2482. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 630

On the top of the cippus there are still traces of a votive gift. It is thus a votive object, as confirmed by the inscription in the Doric dialect and Locrian alphabet: “Oiniadas and Eukelados and Cheimaros dedicated to the goddess.” The goddess in question must be Persephone, since the cippus was found in a sanctuary of this deity.

8 Caduceo

Bronzo

Seconda meta del V secolo a.C.

Brindisi

Inv. 250162. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 672

Sulle due facce dell’impugnatura le iscrizioni:

“(oggetto) pubblico dei Thurii”

“(oggetto) pubblico dei Brindisini”

Tali iscrizioni sottolineano l’alleanza tra la colonia panellenica e la città messapica, alleanza riferibile forse al periodo della lotta di Thurii contro Taranto per la Siritide.

L’oggetto tipico attribuito all’araldo, fu probabilmente dedicato in un santuario.

8 Caduceus

Bronze

Second half of the 5th century BC.

Brindisi

Inv. 250162. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 672

Incised on two faces of the handle:

“Public (object) of Thurii”

“Public (object) of Brundisians”

These inscriptions refer to an alliance between the Pan-Hellenic colony and the Messapic city, possibly dated to the period of Thurii’s conflict with Tarentum for possession of the Siritis.

The object, the typical attribute of heralds, was probably dedicated in a sanctuary.

9 Laminetta

Bronzo

500-475 a.C.

Caulonia (Reggio Calabria)

Inv.120185

Lettera dell’antico alfabeto acheo. Atto in cui Simichos fa donazione di tutti i suoi beni. “E vivo o morto”

L’atto e reso ufficiale dalla mediazione del demiurgo e dei testimoni i cui nomi sono preceduti da sigle.

9 Lamina

Bronze

500-475 BC.

Caulonia (Reggio Calabria)

Inv. 120165

Letters of the ancient Achaean alphabet.

Act by which Simichus “alive or dead”, donates all his property. The act is made official by the mention of the witnesses, whose names are preceded by acronymus.

10 Lamina

Bronzo

500-475 a.C.

Petelia (Catanzaro)

Inv. 2484. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 636

“Dio. Buona Fortuna. Saotis dona a Sikainia la casa e tutto il resto. Damiurgo Paragonas. Garanti Minkon, Armaxidamos, Afatharchos, Onatas, Epikoros”

10 Lamina

Bronze

500-475 BC

Petelia (Catanzaro)

Inv. 2484. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 636

“God. Good Fortune. Saotis donates to Sikainias and all the rest. Damiurge Paragonas. Witnesses Minkon, Armaxidamos, Afatharchos, Onatas, Epikoros”.

11 Piramide fittile con dedica in versi ad Eracle

Terracotta

Fine VI secolo a.C.

San Mauro Forte, presso Metaponto (Matera)

Inv. 112880. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 652

“Nikomachos mi fece. Salve, o Eracle signore, a te mi dedicò il ceramista. E tu concedi a lui di avere una buona fama tra gli uomini”.

Autore dell’oggetto e della dedica è il ceramista Nikomachos, che chiede in cambio al dio di avere una buona fama tra gli uomini.

11 Fictile pyramid with a dedication to Hercules in verses

Terracotta

End of the 6th century BC.

S. Mauro Forte, near Metaponto (Matera)

Inv. 112880. Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 652

“Nikomachos made me. Hail, oh Hercules, lord, the potter dedicated me to you. And so grant him a good reputation among men”.

The maker of the object and author of the dedication is the potter Nikomachos, who asks the god in exchange to be granted a good reputation among men.

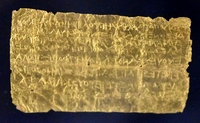

Le Laminette orfiche

Sono definite “orfiche” un gruppo di laminette d’oro, databili tra V secolo a. C. e II d.C. con prescrizioni per il defunto che, grazie alla sua condizione di iniziato (mystes), raggiunge la beatitudine sfuggendo ai dolorosi cicli delle reincarnazioni.

L’orfismo, da Orfeo mitico cantore della Tracia, è una delle più diffuse dottrine misteriche e soteriologiche del mondo antico, che accoglie motivi di altre religioni quali la dionisiaca, la eleusina e le dottrine pitagoriche.

Vi sono due categorie di testi: nella prima, grazie al ricordo delle dottrine apprese in vita l’iniziato sfuggendo al Lethe, cioè all’oblio, può presentarsi alle soglie dell’Ade con la formula «sono figlio della Terra e del Cielo stellato» che gli consentirà di essere identificato e aggregato ad una schiera duplice natura dell’uomo, partecipe dell’elemento divino ma che non si identifica con esso. Nella seconda, alla quale appartengono le laminette esposte, provenienti da due tumuli funerari situati nel territorio di Thurii, il mystes giunto alla presenza di Persefone e di altre divinità infere ricorda la dura esperienza di reincarnazione cui il Fato e Zeus lo hanno condannato per espiare colpe originali e da cui è riuscito a liberarsi attraverso la piena osservanza delle pratiche iniziatiche. Ora che l’anima può dichiarare la sua compiuta catarsi («vengo pura dai puri») e la sua appartenenza alla stirpe divina, il mystes può raggiungere le sedi dei puri ed essere assimilato agli dei («sarai un dio invece che un mortale») conseguendo uno stato di piena beatitudine («capretto mi lanciai verso il latte»).

Orphic laminae

The inscribed gold laminae conventionally called “Orphic” dated between the 5th century BC and 2nd century AD, have the function to enable the deceased to reach, thanks to his condition of initiate (mystes) a privileged situation of beatitude, escaping the painful cycles of reincarnation.

Orphism (from Orpheus, the mythical singer from Thrace) was one of the most diffused mysteric and sotereological doctrines of the ancient world that comprises other cults, such as the Dionysiac and the Eleusinian religion and the Pythagorean doctrines. The texts of the laminae can be divided into two categories: in the first one Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory, has a fundamental role: thanks to the memory of the doctrines he has learned in his lifetime, the initiate, escaping Lethe — i.e. oblivion — can introduce himself at the gates of Hades pronouncing the spell that will allow him to be identified and join the ranks of the chosen:

“I am the son of the Earth and of the starry Sky”. This formula emphasizes the twofold nature of man, who partakes of the Divine but is not fully identified with it. The texts of the second category to which belong all the laminae on exhibit here, found in the two funerary tumuli, in the territory of Thurii — the mystes, having come into the presence of Persephone and the other infernal gods, recounts the harsh experience of the cycles of reincarnation he had been sentenced to by Fate and Zeus to expiate his sins, from which he has finally disengaged himself through his scrupulous observance of mysteric practices. Now that his soul can declare his catharsis completed («I come pure among the pures») and affirm that he belongs to the divine lineage, the mystes can reach the abodes of the pure and becomes as a god («you shall be a god instead of a mortal»), attaining a state of full beatitude: («as a kid I rushed towards the milk»).

12 Lamina

Oro

IV secolo a.C.

Thurii, Tomba del Timpone Grande

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 642

Inv. 111463

“Ma quando l’anima lascia la luce del

sole

Procedi dritto verso destra, tenuta

bene ogni cosa a mente.

Salve, o tu che hai patito una

sofferenza che mai prima provasti:

da mortale sei diventato un dio;

capretto ti lanciasti verso il lette.

Salve, salve, tu che procedi a destra

Verso i prati sacri e i sacri boschi di

Persefone”.

12 Lamina

Gold

4th century BC.

Thurii, Tomb of Timpone Grande

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 642

Inv. 111463

“But when the soul leaves the light of

the sun

Go straight to the right, keeping

everything in mind.

Hail, oh you who has experienced that

which you had never known before:

From mortal you have turned into a

god; like a kid, you rushed towards the

milk.

Hail, hail, you who proceeds to the

right.

Towards the sacred prairies and

sacred woods of Persephone”.

Lamina 13

Inv.111464

Il senso generale del testo, che è certamente di natura religiosa, rimane oscuro. Vi si riconoscono alcuni nomi di divinità, fra cui sembra preminente quello di Demetra.

Lamina 13

Inv. 111464

Inscribed gold lamina, enveloping the preceding one. The general meaning of the text is certainly religious, but is still obscure. Some names of deities are recognizable, among which Demeter seems to have a prominent role.

Lamina 14

Oro

IV secolo a.C.

Thurii, Timpone Piccolo

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 641, 1-3

Inv. 111623

“Vengo pura da puri, o regina degli

Inferi,

Eukles e Eubuleus e altri numi divini.

Dichiaro infatti di appartenere anch’io

alla vostra stirpe beata.

Ma pagai la pena per azioni non

giuste.

Sia che mi domò il Destino e il celeste

lanciatore di fulmini.

Ed ora supplice vengo verso la

veneranda Persefone,

perché benevola mi mandi alle sedi

dei puri”.

14 Lamina

Gold

4th century BC.

Thurii, Timpone Piccolo

Inscriptiones Graecae XIV 641, 1-3

Inv.111623

“I come pure from the pure, o queer

of the underworld,

Eukles and Eubuleus, and other

divine numina.

I also avow that I am of your blessed

race.

But I have paid the penalty for action

unrighteous,

and Fate subdued me, and the

heavenly thunderbolt thrower.

And now I come a suppliant to the

venerable Persephone,

that she may benevolently send me to

the abodes of the pure.”

Lamina 15

Inv.111624

“Vengo pura da puri, o regina degli

Inferi,

Eukles e Eubuleus e quanti altri numi

divini siete.

Dichiaro infatti di appartenere anch’io

alla vostra stirpe beata.

Ma pagai la pena per azioni non

giuste,

e mi (domò) il Destino e il celeste

lanciatore di fulmini.

Ed ora vengo presso Persefone che

esaudisce,

perché mandi alle sedi dei puri”.

15 Lamina

Inv.111624

“I come pure from the pure, o queen

of the underworld,

Eukles and Eubuleus, and as many

other divine numina you are.

I also avow that I am of your blessed

race.

But I have paid the penalty for actions

unrighteous,

and Fate (subdued) me, and the

heavenly thunderbolt thrower.

And now I come to Persephone, who

grants wishes,

that she may send me to the abodes

of the pure.”

Lamina 16

Inv. 111625

«Vengo pura da puri, o regina degli

Inferi,

Eukles e Eubuleus ed altri numi divini.

Dichiaro infatti di appartenere anch’io

alla vostra stirpe beata.

Ma mi domò il Destino e il celeste

lanciatore di fulmini.

Volai via da doloroso ciclo grave di

affanni.

E con piedi veloci ascesi alla

desiderata corona,

mi immersi nel grembo della Signora

regina degli Inferi,

discesi dalla desiderata corona con

piedi veloci.

“O felice, e beatissimo, sarai un dio

invece che un mortale”

Capretto mi lanciai verso il latte».

16 Lamina

Inv. 111625

“I come pure from the pure, o queen

of the underworld,

Eukles and Eubuleus, and other

divine numina.

I also avow that I am of your blessed

race.

But Fate subdued me, and the

heavenly lighting bolt thrower.

I flew out of a sorrowful, weary cycle

of griefand on quick feet I ascended to

the coveted crown,

I sank into the bosom of the Mistress,

the queen of the underworld

I came down from the coveted crown

on quick feet.

“O happy and blessed one, you shall

be a god instead of a mortal.”

Like a goat kid I rushed towards the

milk.”

17 Statua naoforo di Uahibramerineit

Basalto. Epoca Tarda, XXVI dinastia (664-525 a.C.)

Collezione Farnese, inv. 1068

17 Naophore of Wahibremeryneith

Basalt. Late Period, 26th dynasty (664-525 BC)

Farnese collection, inv. 1068

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis