Indice dei Musei

presenti in miti3000

Napoli Museo Nazionale - Piano - 1 - Sezione Epigrafi

Testo

MANN - Piano meno uno - Sezione Epigrafi

Sala CLII

POMPEI

Forme di occupazione del pianoro di Pompei risalgono alla fine del VII secolo a. C. quando nella regione era preponderante l'influenza degli Etruschi. L'area fu cinta da mura - più volte restaurate e ricostruite durante la storia della città - sfruttando le difese naturali del sito, a prescindere dall'estensione dell'abitato originario.

Occupata dai Sanniti (V secolo a.C.), risparmiata dalla guerra annibalica (218-202 a.C.), di cui molto soffrì Nocera, Pompei fu ammessa in qualità di alleata fedele di Roma, ai privilegi della città dominante e, nel II secolo a.C., fiorì notevolmente.

Le iscrizioni pubbliche osche attestano che i magistrati sono di famiglie aristocratiche sannite, ma la struttura amministrativa è profondamente condizionata da Roma. Il magistrato supremo (meddix tuticus) perde le sue prerogative militari e diplomatiche per occuparsi esclusivamente dell'amministrazione cittadina: finanze, appalto e collaudo di lavori pubblici.

Sull'esempio romano compaiono magistrati minori: due questori, per l'amministrazione finanziaria e per lavori da eseguire con fondi speciali su delibera di una delle due assemblee cittadine (kombennio e komparakion) e due edili preposti soprattutto alla costruzione e alla manutenzione delle strade.

Fenomeni analoghi interessano tutte le comunità sannite, ma la documentazione pompeiana è una delle più nitide in proposito.

Le epigrafi riflettono anche gli interventi urbanistici che danno a Pompei caratteri e strutture tipiche della città romana, delineando già la fisionomia preservata dall'eruzione. A questo periodo risalgono il Foro rettangolare e la risistemazione dell'area circostante. La ricca aristocrazia sannita esibisce abitazioni splendide: l'esempio più illustre è la Casa del Fauno, che nel II secolo è ampliata fino a coprire una superficie di circa 3000 mq., e sontuosamente decorata di finissimi mosaici figurati. La Guerra Sociale (91-89 a.C.) e la guerra civile tra Mario e Silla (87-82 a.C) coinvolsero Pompei e le altre città sannite della Campania meridionale, tutte di parte mariana. Silla, riuscito vittorioso, stanziò nella regione i suoi veterani. Nell'80 a.C. fu dedotta una colonia a Pompei. Questa soluzione implicò confische che sconvolsero gli equilibri della comunità e il primato politico e economico della sua aristocrazia segnando la fine di un'epoca della storia di Pompei.

Pompeii

The first settlements in the Pompeii plateau took place during the late 7th century BC when the influence of the Etruscans was ruling in the region. The area was surrounded by walls - restored and rebuilt several times during the history of the town - taking advantage of the natural defenses of the site, regardless of the extension of the original town.

Occupied by the Samnites (5th century BC), spared from the war against Hannibal (218-202 BC), which much affected Nuceria, Pompeii was given as a faithful ally of Rome the privileges of the dominant town and, in the 2nd century BC, it flourished considerably.

The Oscan public inscriptions attest that public charges are from Samnite aristocratic families, but the administrative structure is deeply influenced by Rome. The chief magistrate (meddix tuticus) loses its military and diplomatic powers, to deal exclusively with the town administration: finance, procurement and testing of public works. The figures of minor charges were created, inspired by Roman example: two quaestors were responsible for the financial administration and for works to be carried out with special funds after deliberation of one of the two town assemblies (kombennio and komparakion), while two aediles were mainly in charge of the construction and maintenance of roads. Similar phenomena regard all the Samnite communities, but the Pompeian documentation is one of the clearest about this topic.

The inscriptions also reflect the urban interventions that give Pompeii features and structures typical of a Roman town, outlining the town plan as it was then preserved by the eruption. The rectangular Forum and the rearrangement of the surrounding area belong to this period. The rich Samnite aristocracy shows its beautiful houses: the most outstanding example is the House of the Faun, that, during the 2nd century was expanded and covered an area of about 3000 square meters. It is sumptuously decorated with the finest figurative mosaics.

The Social War (91-89 BC) and the Civil War between Marius and Sulla (87-82 BC) involved Pompeii and other Samnites towns in Southern Campania, all of them allied with Marius. Sulla was victorious and settled his veterans in the region. In 80 BC he established a colony in the Pompeii area, this way causing confiscations that shook the community balance and the political and economic supremacy of its aristocracy marking the end of an era in the history of Pompeii.

NOLA

Città degli Ausoni secondo Ecateo di Mileto (che scriveva intorno al 500 a.C.), fondazione di coloni calcidesi secondo una tradizione sviluppatasi sulla scia dei suoi stretti rapporti con le città greche della costa, Nola si trova, come Capua, nell'orbita di influenza etrusca. Secondo Catone, la città era stata occupata dagli Etruschi poco dopo la fondazione di Capua. Il periodo di maggiore splendore per la città fu quello compreso tra il VI e il I secolo a.C., come dimostrano i materiali provenienti dalle necropoli.

Alla fine del V secolo a.C. la città, che forse in precedenza era chiamata Hyria, segue il destino degli altri centri della pianura campana e cade sotto il potere dei Sanniti, che le attribuiscono il nome di Novia (la Nuova). Nel 328 a.C., però, viene sconfitta dalla stessa Roma, di cui diventa allora una civitas foederata.

Fino alla guerra annibalica (218-202 a.C.), Nola resta fedele a Roma, ma dopo la sconfitta di Canne (216 a.C.), temendo che la città passasse dalla parte di Annibale, viene occupata da Claudio Marcello, i capi popolari vengono messi a morte e la costituzione cittadina viene riformata in senso aristocratico. Durante la guerra tra Roma e gli alleati italici (91-82 a.C.), Nola, che ospitava una guarnigione romana, viene occupata dal capo sannita Gaio Papio Mutilo (90 a.C.). L'anno successivo Silla, che aveva riconquistato gran parte della Campania, pone l'assedio alla città. Nello scontro tra Mario e Silla, i Sanniti si erano schierati con la fazione mariana. Dopo la loro sconfitta presso la Porta Collina (82 a.C.), Nola è tra gli ultimi centri a soccombere. Nell'80 a.C. la città viene presa da Silla che per ritorsione vi deduce una colonia di suoi veterani.

Della città antica non rimangono oggi che pochi resti - quelli dell'anfiteatro e alcuni monumenti funerari - grazie alla continuità di occupazione del sito, mai interrotta fino all'età moderna, testimoniata, inoltre, dalle epigrafi e dagli elementi architettonici reimpiegati nel centro cittadino.

Nola

According to Hecataeus of Miletus (who wrote around 500 BC) the town was founded by the Ausones, while a different tradition refers that Chalcidian settlers founded it, owing to its close relations with the Greek towns of the coast. Nola was, as Capua, in the sphere of Etruscan influence. According to Cato, the town was occupied by the Etruscans shortly after the foundation of Capua. The town reached its greatest splendor between the 6th and the 1st century BC, as showed by the archeological finds coming from the necropolis.

At the end of the 5th century BC the town, perhaps previously called Hyria, followed the fate of the other centers in the Campania plain and was conquered by the Samnites, that named it Novia (New). In 328 BC, however, it was defeated by Rome, becoming then a civitas foederata to it.

Until the war against Hannibal (218-202 BC), Nola remains true to Rome, but after the defeat of Cannae (216 BC), fearing that the town might pass on Hannibal's side, it was occupied by Claudius Marcellus, its leaders were sentenced to death and the town constitution was reformed in favour of aristocracy. During the war between Rome and the Italic allies (91-82 BC), Nola, which hosted a Roman garrison, was occupied by the Samnite leader Gaius Papius Mutilus (90 BC).

The following year Sulla, who had regained much of Campania, laid siege to the town. In the fight between Marius and Sulla, the Samnites had sided with Marius. After their defeat at Porta Collina (82 BC), among the other centers Nola was the last to succumb. In 80 BC the town was taken by Sulla that founded there a colony of his veterans as a retaliation.

Only few remains of the ancient town can be seen nowadays - the ones in the amphitheater and some funerary monuments. This is due to the fact that the site has been constantly occupied until modern times, as also witnessed by the epigraphs and the architectural elements reused in the town center.

GLI IRPINI

L'Irpinia corrisponde all'attuale provincia di Avellino e alla parte meridionale di quella di Benevento. La sua posizione ne faceva nell'antichità un crocevia tra l'alta valle del Volturno e la valle del Calore che, alla Sella di Conza, si apriva verso l'importante via naturale del fiume Sele.

Quella degli Irpini era una delle quattro tribù del Sannio menzionate dagli scrittori antichi, che sottolineavano la maggiore vicinanza degli Irpini ai Lucani, facendo derivare l'etnico dei due popoli dalla parola "lupo" - (h)irpus in osco, lykos in greco. Questa teoria, in passato accolta da alcuni studiosi, è stata poi sconfessata dal riesame delle vicende storiche e delle caratteristiche culturali degli Irpini che rientrano, dunque, a pieno titolo tra i Sanniti.

La documentazione archeologica è piuttosto scarsa e consiste essenzialmente in tombe databili tra la fine del V e la fine del IV sec. a.C.. Più ampio appare il quadro culturale testimoniato dalla documentazione epigrafica di Aeclanum, ubicata in località Grotte, frazione di Mirabella Eclano. Qui è attestato il culto di Marte, di Fatuus e di Mefite; quest'ultimo localizzato in un'area extraurbana. Questo culto si collega a quello più caratteristico praticato nella Valle d'Ansanto, nei pressi di Rocca San Felice in provincia di Avellino. Del santuario indigeno rimane la testimonianza degli ex-voto E delle decorazioni architettoniche, che attestano la continuità d'uso dal IV sec. a.C. fino al II a.C.. La dea Mefite era una divinità ctonia, il cui culto era legato alle caratteristiche naturali del luogo, terreni vulcanici con pozze e laghetti che emanavano esalazioni maleodoranti. Anche ad Aeclanum potrebbe esservi relazione con un luogo in cui si verificavano esalazioni, di cui rimane il ricordo nel toponimo Acquaputrida, attribuito in passato a Mirabella.

La diffusione del culto dclla dea in altre zone dell'Irpinia - oltre che ad Aeclanum è attestato ad Ariano Irpino - va attribuita alla celebrità del santuario principale, che svolse il ruolo di santuario "federale" degli Irpini.

The Hirpini

The Hirpini were one of the four tribes of the Samnium mentioned in the ancient literary sources. The Roman historical tradition insisted on their being a distinct entity with respect to the rest of the Samnites. Their proximity to the region of Lucania, and the probable derivation of the name of both peoples, Lucani and Hirpini, from the word "wolf"- (h)irpus in Oscan and lykos in Greek - was considered to be evidence in favour of this theory, which in the past was accepted by modern scholars as well. An objective examination of the history and culture of the Hirpini however excludes this hypothesis: the Hirpini were Samnites by full right.

The archaeological documentation concerning the tribe of the Hirpini is rather scarce, and consists essentially of graves dated between the end of the 5th and the end of the 4th century BC. Their culture, on the other hand, is better attested by the epigraphs of Aeclanum. The ancient city was located in the area of Grotte al Passo di Mirabella in the township of Mirabella Eclano, and was one of the most important centers documenting the existence of cultus of Mars and Fatuus and the presence of an extra-urban sacred area dedicated to Mephitis. The cult of the latter deity is the most characteristic of inland Hirpinia. It was celebrated in the sanctuary of the goddess Mephitis in the Valley of the Ansanto, near Rocca San Felice in the province of Avellino. Mephitis was a chthonic deity, whose cult was connected to the natural characteristics of the places where it was celebrated, i.e. volcanic areas with pools exhaling ill - smelling fumes.

The diffusion of the cult of Mephitis into other parts of Hirpinia - it is attested in Ariano Irpino as well as Aeclanum - must have been a consequence of the popularity of this, its main sanctuary, probably the "federal" sanctuary of the Hirpini.

IL SANNIO

I Sanniti Pentri e Frentani costituivano entità politiche diverse. Il loro territorio corrisponde al Molise interno e a parte dell'Abruzzo in base alla divisione operata dai Romani, che inclusero i Pentri nella tribù Voltinia e, successivamente, nella IV Regione augustea. Per i Romani della tarda repubblica il termine Samnites indicava soltanto la tribù dei Pentri e il Samnium era il loro territorio. Sono qui esposte alcune iscrizioni provenienti da Pietrabbondante, Alfedena, Agnone e Sepino.

Pietrabbondante: qui sorgeva il più importante centro cultuale dei Sanniti Pentri. Le iscrizioni provengono tutte dal santuario in località Calcatello: un complesso teatro-tempio (fine II- inizio I sec. a.C.) dedicato al culto della Vittoria (tempio B). Il teatro era anche luogo di adunanza politica. Annessa al santuario era una domus publica, con un sacrario ad Ops Consiva. Nell'ultima fase edilizia il complesso divenne santuario della touto, cioè di tutta la nazione dei Sanniti Pentri; fu riedificato poco prima della Guerra Sociale (91-88 a.C.), l'ultimo scontro con Roma, che sarà duramente pagato dai Sanniti. In seguito gli edifici religiosi non ricevettero alcuna cura, e la domus publica divenne una residenza privata, occupata dalla famiglia dei Socelli.

Aufidena: a Castel di Sangro, dove in età romana fu costituito il municipio, rimangono i resti di quella che era stata una roccaforte in posizione strategica sulla via d'accesso al Sannio dalla regione dei Peligni e dalla costa adriatica. Presso l'odierna Alfedena esisteva un altro insediamento di epoca sannitica. Non è chiaro se in epoca sannitica il toponimo Aufidena corrispondesse al sito di Castel di Sangro o all'attuale Alfedena, che in età alto medievale assunse il nome di Aufidena.

Agnone: il moderno centro di Agnone si trova a breve distanza dal santuario di Cerere di località Fonte Romito, da cui proviene la famosa Tavola di Agnone (ora conservata al British Museum di Londra), che contiene le norme relative ai riti e indicazioni circa la condizione giuridica del santuario.

Sepino: il nome significa "luogo recintato" e allude alla funzione originaria di luogo di sosta per le greggi durante la transumanza. La sua posizione all'incrocio di strade che collegavano la Sabina con l'area apula e la pianura con le montagne del Matese ne favorì la nascita forse già prima del IV sec. a.C. e spinse i Romani a fondarvi un municipio.

The Samnium

The Pentri and the Frentani constituted different political entities. On the evidence of the re-organization of the tribes on the part of the Romans, who included the Pentri in the Voltinia tribe and, later on, in the 4th Augustan Region, their territory most have included inland Molise and part of Abruzzo. The Romans of the late Republican period used the term Samnites only to refer to the tribe of the Pentri, whose territory they called Samnium.

The inscriptions on exhibit here were found in Pietrabbondante, Alfedena, Agnone and Sepino.

Pietrabbondante: this is the site of the most important cult center of the Pentrian Samnites.The inscriptions were all found in the sanctuary in Calcatello: a theater-temple dedicated to Victory (temple B), dated between the end of the 2nd and the beginning of the 1st century BC.The theater had the function of a meeting place (comitium), connected to the temple and erected on a consecrated area. Thereby, the site assumed, in its last building phase, the characteristics of a sanctuary of the touto, i.e. of all the tribe of the Pentrian Samnites. It was in a magnificent position, dominating several valleys, and visible from far away, a landmark for all the surrounding mountain district. The compound was rebuilt soon before the last conflict with Roma (Social War), which was mainly sustained by the Samnites themselves, who paid a heavy cost for their defeat. The abandoning of this sanctuary in the 1st century BC is a reflection of those events.

Aufidena: in Castel di Sangro - where, during the Roman age, a municipium was established - there still are conspicuous remains of what had once been a stronghold in a strategic position along the route that gave access to Samnium from the region of the Paeligni and from the Adriatic coast. Near present-day Alfedena, however, there existed another settlement of the Samnite period. During the early Middle Ages this town assumed the name of Aufidena, so that it is not clear whether the toponym Aufidena referred, during the Samnite period, to the site of Castel di Sangro.

Agnone: the modern center of Agnone is within the ancient territory of the Pentri, at a short distance from the sanctuary of Ceres in Fonte Romito, where the famous Agnone Table (now kept in the British Museum in London) was found. This table contains the norms regulating the rites performed in the sanctuary, and indications concerning its.

ISCRIZIONI NORD-SABELLICHE

Sotto la denominazione di Nord-Sabelliche vengono raccolte le iscrizioni pertinenti a quelle tribù di lingua italica che si trovavano geograficamente in posizione intermedia tra Umbri e Sanniti e che non costituirono mai un organismo politico unitario, tale da procurare ad esse né un etnico comune né tantomeno una koinè linguistica. I dialetti parlati non assumono una tipologia uniforme ma si avvicinano ora all'osco ora all'umbro. Le epigrafi esposte rappresentano parte dei dialetti di questo gruppo: il peligno, che offre maggior numero di testimonianze, tra le quali assume un rilievo particolare l'epitaffio poetico da Corfìnio (n. 29), la cui struttura formale si dimostra autonoma rispetto all'uso metrico romano, il vestino, che nell'epigrafe di Navelli (n. 28) si presenta come una lingua commista di elementi dialettali e di latino regionale, prova della precoce penetrazione del latino nel territorio dei Vestini già dal III sec. a.C.; il volsco, che ha nella tavoletta di Velletri il suo unico documento (n. 33).

La lingua dei Volsci fornisce elementi utili per riconoscente l'origine che, controversa negli autori antichi, viene attualmente considerata appenninica, più precisamente dall'area umbra. È da qui che i Volsci migrarono verso sud nel corso del VI sec. a. C., per insediarsi nella valle del Liri e nella regione pontina.

Le iscrizioni relative alle culture protostoriche della fascia centrale dell'Italia prospiciente il mar Adriatico possono definirsi paleosabelliche. Si tratta di un gruppo di iscrizioni italiche fra le più antiche, che utilizzano un alfabeto locale con influenze etrusche e una scrittura con ductus serpentino.

L'umbro è tradizionalmente considerato come uno dei due poli linguistici in cui si struttura l'italico, opposto all'osco. La lingua umbra è conosciuta principalmente dalle Tavole Iguvine, tavole di bronzo con testi a contenuto religioso, iscritte in parte in alfabeto etrusco, adottato dall'umbro, parte in alfabeto latino.

Nord-Sabellic inscriptions

The definition of "Nord-Sabellic" used for those tribes speaking Italic languages who occupied an intermediate geographic position between the Umbrians and the Samnites. These tribes never came together to form a single political organism, and hence never had a common ethnic name or formed a linguistic koiné. The dialects they spoke were diverse, some being closer to Umbrian, others to Oscan. Most are exemplified by the epigraphs on exhibit here, including Paelignan, the dialect represented by the most examples: the poetic epitaph from Corfinium (n. 29) is especially remarkable, in that its formal structure is autonomous from Roman metrics; Vestine, exemplified by the epigraph from Navelli (n. 28) which, however, combines dialect and regional Latin, giving evidence of the precocious penetration of Latin, as early as the 3rd century BC, into the territory of the Vestini; Volscian, the only document of which is the Velletri tablet (n. 33). The origin of the Volscian language was a moot point among ancient authors, while today it is thought, on the basis of internal linguistic evidence, to be of Apenninic origin, and more precisely from the Umbrian area. The Volscians migrated towards the south from Umbria in the course of the 6th century BC, to settle in the valley of the Liri and in the Pontine region.

The inscriptions belonging to the protohistoric cultures of the Adriatic side of central Italy are conventionally labelled "Middle Adriatic" or "Paleosabelliche". This group of epigraphs is one of the most ancient. It is written in a local alphabet with Etruscan influences, and the writing has a serpentine ductus.

Umbrian is traditionally considered to be one of the two linguistic poles of the Italic language family, the other being Oscan. Umbrian is mainly known from the Iguvian Tablets, bronze tablets inscribed with religious texts, part written in Etruscan alphabet, (which had been adopted by the Umbrians), and part in Latin alphabet.

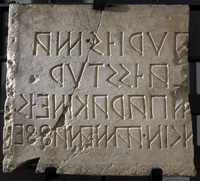

1 Epigrafe rupestre

Calco in gesso

Punta della Campanella

Calco dell'epigrafe rupestre scoperta nell'agosto 1985 a Punta della Campanella nel territorio di Massalubrense (Napoli)

Testo in lingua osca

Scrittura da destra a sinistra

Datazione incerta tra III e I secolo a.C.

m. gaaviis m . l. pítakiis . m/l. appuliis . ma. medd[í]ks . menereviiús/ esskazsiúm . ekúk. upsannúm/ dedens íusúm . prúfattens

«M. Gavio (figlio di) M., L. Pittaco (figlio di) M., L. Apulo (figlio di) Ma., meddices (del santuario di) Minerva, fecero sì che si facesse questa scala; essi stessi approvarono».

L'iscrizione, incisa nella roccia, si trovava lungo la scala che univa l'approdo al santuario di Atena a Punta della Campanella. Il promontorio, noto nell'antichità come Capo Ateneo, è il punto estremo della penisola sorrentina, e con la prospiciente l'isola di Capri, costituisce l'ingresso orientale al golfo di Napoli. L'importanza di questo passaggio nelle antiche rotte è confermata dal fatto che nella penisola sorrentina era vivo anche il culto delle Sirene, semidivinità collegate alle insidie della navigazione. Non stupisce, quindi, che qui fosse venerata una divinità legata anche alla protezione dei naviganti. Ancora nel I sec. d.C. agli occhi dell'aristocrazia romana che qui possedeva numerose e splendide ville, la penisola sorrentina era caratterizzata dagli echi di questi culti. Secondo il geografo greco Strabone (inizi I sec. d.C.) il tempio di Atena era stato fondato da Ulisse di ritorno da Troia. La ricerca archeologica fa risalire le prime fasi di un culto a Punta della Campanella alla metà del VI sec. a.C.. Le più consistenti testimonianze archeologiche - soprattutto ex-voto - del culto di Atena si datano a partire dal IV sec. a.C. quando i Sanniti già da tempo dominavano la Campania. Questi dati pongono difficili problemi sulla presenza dell'elemento greco in un'area (la penisola sorrentina) in cui l'archeologia ci rivela preponderante l'elemento etrusco; e sul ruolo dei nuovi dominatori sanniti in riferimento al culto di Atena/Minerva.

L'iscrizione ricorda un'opera appaltata e collaudata da tre personaggi definiti "meddices di Minerva", investiti, cioè, di non ben precisabili funzioni politiche e/o amministrative riguardo al santuario, ed è comunque la prova della radicata presenza sannita nella sua gestione, mentre si discute se contenga indizi dell'influsso di Roma.

1 Rock inscription

Plaster cast

Punta della Campanella

Mould of the rock epigraph discovered in August 1985 at Punta Campanella in Massa Lubrense area (Naples).

Text in the Oscan language

Writing from right to left.

Uncertain dating between 3rd and 1st century BC.

m. gaaviis m . l. pítakiis . m/l. appuliis . ma. medd[í]ks . menereviiús/ esskazsiúm . ekúk. upsannúm/ dedens íusúm . prúfattens

"M. Gavius (son of) M., L. Pittacus (son of) M., L. Apulius (son of) Ma., meddices (of the sanctuary of) Minerva, made the building of this staircase possible; they themselves approved it."

The inscription was engraved in the rock along the staircase that connected the landing place to the sanctuary of Athena to Punta Campanella. The promontory, known in ancient times as Cape Athenaeus, is the extreme tip of the Sorrento peninsula, and with the imposing island of Capri, is the Eastern entrance to the Bay of Naples. The importance of this passage along ancient routes is confirmed by the fact that in the Sorrento peninsula was alive the cult of the Sirens, demigoddesses connected to the hidden dangers of navigation. No wonder, then, that here a deity related to the protection of sailors was also worshipped. Even in the 1st century A.D. the Roman aristocracy, that here had numerous and splendid villas, believed that an important feature of the Sorrento peninsula were the echoes of these cults. According to the Greek geographer Strabo (early 1st century A.D.) the temple of Athena was founded by Ulysses on his way back from Troy. Archaeological research dates back the early stages of a cult in Punta Campanella to the mid-6th century B.C. The most significant archaeological evidence of the cult of Athena - especially votive offerings - date from the 4th century B.C. when the Samnites had been dominating the Campania for a long time. These data make it difficult to have a full knowledge of the Greek presence in this area (the Sorrento peninsula) where archeological research attests an overwhelming Etruscan presence; it is also not well defined the role of the new Samnites rulers in relation to the cult of Athena/Minerva. The inscription reminds a work contracted out and tested by three characters called "meddices of Minerva", who had not clear political and/ or administrative functions connected to the sanctuary. However the inscription proves the well rooted presence of the Samnites in the management of the sanctuary, while scholars are still discussing whether it contains evidence of the influence of Rome.

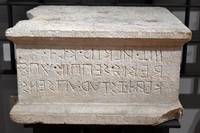

2 Mensa di altare

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Marmo

150-90 a.C.

Ercolano

Inv. 2540 (Vetter 107)

Lato A. "Sono di Herentas".

Lato B. "L Slabio (figlio di) L. Aucilo meddix pubblico a Herentas Ericina pose".

L'oggetto afferma la sua appartenenza ad Herentas, divinità italica corrispondente ad Afrodite-Venere. Ad Ercolano è venerata, certo per influenza romana, la Herentas (Venere) di Erice presso Trapani, dove la dea aveva un famosissimo santuario di origine punica ma collegato altresi, all'epos, alle ascendenze troiane di Roma.

2 Altar slab

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Marble

150-90 BC.

Herculaneum

Inv. 2540 (Vetter 107)

Side A."I am of Herentas".

Side B. "L. Slabius (son of) L. Aucilus public meddix erected to Herentas of Eryx".

The objects states that it belongs to Herentas, an Italic deity corresponding to Aphrodite-Venus. In Herculaneum, doubtlessly due to Roman influence, the Herentas of Eryx (near Trapani) was adored, where the goddess had a very famous sanctuary, of Punic origin but connected in the epic tradition to Rome's Trojan ascendancy.

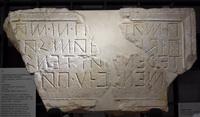

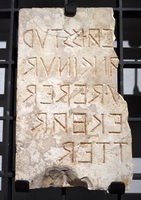

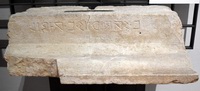

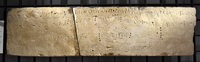

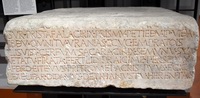

3 Iscrizione commemorativa del lavori per la via Salina

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Fine III-II secolo a.C.

Pompei

Inv. 2546/110871 (Vetter 9-10)

"P. Matio (figlio di) P. e Nimsio Maraio (figlio di P.) edili, la Via Salina delimitarono e … la via è larga … pertiche".

La Via Salina doveva essere in relazione con la Porta Salina, nota da altre iscrizioni, forse da identificare con l'attuale Porta di Ercolano: sulla costa in direzione di Torre Annunziata (e quindi di Ercolano) si trovavano le "Saline di Ercole". L'azione degli edili potrebbe riferirsi alla delimitazione tra carreggiata e marciapiede, o alla delimitazione della via, in quanto area demaniale, rispetto alle aree limitrofe.

3 Commemorative inscription for the works of the via Salina

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

End of the 3rd-2nd century BC.

Pompeii

Inv. 2546/110871 (Vetter 9-10)

"P. Matius (son of) P. and Nimsius Maraius (son of P.), aediles, delimited the Via Salina (Salina road) and … the road is wide … perticae"

.The Via Salina must have had a relationship with the Porta Salina ("Salina Gates"), known from other inscriptions, and possibly to be identified with present day Porta di Ercolano ("Herculaneum Gates") as, along the coast in the direction of Torre Annunziata (and hence of Herculaneum), were the "Saline di Ercole" ("Salterns of Hercules"). The action of the aediles referred to in the inscription might therefore have concerned the delimitation of roadway from the sidewalk, or of the road, in its quality of public area, from the adjacent areas.

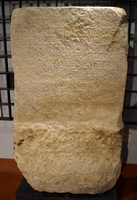

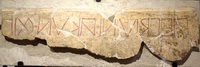

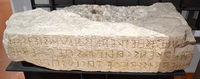

4 Cippo viario

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Fine III-II secolo a.C.

Pompei, originariamente situato nell'androne della Porta Stabiana

Inv. 114466 (Vetter 8)

"M. Siuttio (figlio di) M.N. Pontio (figlio di) M. Edili questa via delimitarono fino all'estremità inferiore della (via) Stabiana. La via fu delimitata per pertiche dieci. Gli stessi la via pompeiana delimitarono per pertiche tre fino alla cella di Giove Meilichio.

Queste vie e la via giovia e il decuviare con gli auspici del meddix pompeiano dal fondo fecero. Gli stessi edili approvarono".

La Via Stabiana era il maggiore asse cittadino nord-sud. L'identificazione della Via Pompeiana dipende da quella del tempio di Giove Meilichio (dolce come il miele), individuato in area extraurbana. La Via Giovia non è nota; se "decuviare" significa "decumano" (asse viario maggiore est-ovest), potrebbe essere identificata con Via dell'Abbondanza.

4 Cippus

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

End of the 3rd-2nd century BC.

Pompeii, originally situated in the hall of the Porta Stabiana

Inv. 114466 (Vetter 8)

"M. Siuttis (son of) M., N. Pontius (son of) M. Aediles of this road, delimited it up to the lower end of the (via) Salina.

The road was delimited for ten perticae. The same delimited the Via Pompeiana for three perticae up to the cell of Jupiter Meilichios. They did these roads and the Via Iovia and the decuviare from the bottom, with the auspices of the Pompeian meddix".

The Via Stabiana was the major north-south axis of Pompeii. The identification of the Via Pompeiana depends on that of the temple of Jupiter Meilichios ("sweet as honey"), outside the city. The Via Iovia is not known from other sources. If "decuviare" means "decumanus" (major east-west road), it could refer to Via dell'Abbondanza.

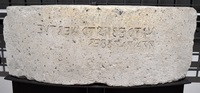

5 Orologio solare

Marmo

Seconda metà del II secolo a.C.

Pompei, dalle Terme Stabiane (1854)

Inv.2541 (Vetter 12)

“Maras Atinio (figlio di) Maras, questore, con il denaro delle multe per delibera dell’assemblea fece sì che si facesse”.

L’orologio solare fu uno dei tanti prestiti del mondo greco a quello romano e il raffinato esemplare pompeiano testimonia il gusto ellenistico cui si adeguarono anche le “Terme Stabiane” (nome moderno che si riferisce alla posizione lungo la Via Stabiana), che nel II secolo a.C. sostituirono un precedente impianto molto più rudimentale.

Ritrovato a Pompei il 23 settembre 1854 nelle Terme stabiane, serviva a gestire i turni di accesso. Il quadrante è una porzione di cono circolare retto, superiormente delimitata da una curva iperbolica. L’orologio presenta tre curve diurne circolari, parallele tra di loro.

Le curve dei solstizi e degli equinozi risultano divise ciascuna in 12 parti uguali per il tracciamento delle undici linee orarie, ottenute congiungendo le corrispondenti partizioni dei tre circoli diurni.

Le ore segnate sono quelle “diseguali”.

Un’epigrafe in lingua osca individua il questore Mara Atinio come promotore della costruzione dell’orologio:

Mara Atinio, figliuol di Mara, questore col danaro delle multe per decreto de’ decurioni fece fare

Altre informazioni nella pagina dedicata agli orologi solari

5 Solar clock

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Marble

Second half of the 2nd century BC.

Pompeii, found in the Thermae Stabiane (1854)

Inv. 2541 (Vetter 12)

“Maras Artinius (son of) Maras, quaestor, with the money from the fines, by resolution of the assembly, had (this) made”.

Solar clocks were one of the many contributions of the Greeks to the Roman world, and this refined Pompeian specimen bears witness to the Hellenistic taste to which the Terme Stabiane (a modern name referring to their position along the Via Stabiana) conformed. The Terme Stabiane replaced an earlier, much less sophisticated facility in the 2nd century BC.

Discovered at Pompeii on 23 September 1854 in the Stabian Baths, it was used to regulate the turns for entering the complex.

The dial is a portion of a right circular cone, bounded on the upper side by a hyperbola.

The clock has three circular day curves that are parallel to each other.

The day curves are the lines cast by the shadow of the gnomon over the course of a whole day. The arcs of the solstices and equinoxes are each divided into 12 equal parts to plot the eleven hour lines, obtained by joining the corresponding partitions of the three day curves.

The hours marked are “unequal hours”.

An inscription in Oscan reveals that the quaestor Maras Atinius commissioned the construction of the sundial:

Maras Atinius, son of Maras, quaestor, has, by decision of the council, commissioned the establishment (of the sundial) from the money raised from fines.

6 Striscia di pavimento

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Ardesia

Seconda metà del II secolo a.C.

Pompei, dal Tempio di Apollo (1883)

Inv. 113398 (Vetter 18)

“Ovio Campanio… questore, per delibera dell’assemblea, con il denaro di Apollo… fece sì che si facesse”.

L’epigrafe si riferisce al rifacimento del pavimento del Tempio di Apollo con il denaro delle offerte dei fedeli. Il tempio risale al VI secolo a.C.; nel II secolo a.C. fu completamente ricostruito secondo modelli ellenistici e organicamente inserito nel tessuto dell’area del nuovo Foro.

6 Strip of slate floor

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Schist

Second half of the 2nd century BC.

Pompeii, from Temple of Apollo (1883)

Inv. 113398 (Vetter 18)

“Ovius Campanius … quaestor, by decree of the assembly, with the money of Apollo… had (this) made”.

The epigraph refers to the restoring of the floor of the Temple of Apollo with the money of the offerings of the faithful. This temple was built in the 6th century BC.; in the 2nd century BC., it was completely rebuilt according to Hellenistic canons, and planned so as to fit organically into the area of the new Forum.

7 Intervento di un questore

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Pompei, Tempio di Apollo (1818)

Inv. 2545(Vetter 19)

“Il questore su delibera (dell’assemblea) fece sì che si facesse (con il denaro … lo stesso) approvò”.

7 A quaestor intervention

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Pompeii, Tempio di Apollo (1818)

Inv. 2545 (Vetter 19)

“The quaestor, by decree (of the assembly), had (this) made (with the money … the same) approved”.

8 Testamento di Vibio Adirano

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

I secolo d.C.

Pompei, Palestra Sannitica, murata in una parete (1797)

Inv. 2542 (Vetter 11)

“V(ibio) Adirano (figlio di) Vibio questo danaro alla vereia pompeiana lasciò in testamento. Con quel denaro V(ibio) Vinicio (figlio di) M(araio), questore pompeiano, questo edificio per delibera dell’assemblea fece sì che si facesse. Egli stesso approvò”.

La Palestra Sannitica, alle spalle della cavea del Teatro Grande, e adiacente all’area del Tempio di Iside, è troppo piccola per essere un impianto sportivo vero e proprio: dovette piuttosto essere un luogo di riunione della vereia pompeiana, chiaramente diventata un’istituzione civica sottoposta al controllo delle autorità cittadine.

8 Testament of Vibio Adirano

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

1rst century AD.

Pompeii, Palestra Sannitica, found in the walling (1797)

Inv. 2542 (Vetter 11)

“V(ibius) Adanus (son of) Vibius left this money as inheritance to the Pompeian verehia. With taht money V(ibius) Vinicius (son of) M(araius), Pompeian quaestor, had this building made by decree of the assembly. He himself approved”.

The Palestra Sannitica, behind the cavea of the Great Theater and adjacent to the area of the Temple of Isis, is too small to have been a real gymnasium. It must rather have been a meeting place for the Pompeian vereia, which, in this period, had clearly become a civic institution under the control of the town authorities.

9 Frammento di intonaco con iscrizione incisa e dipinta in rosso

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Teano, Santa Maria di Loreto (1793), da Pompei secondo Finati 1823

Inv. 2549 (Vetter 70)

“Audia (figlia di) Nimsio di anni 112”.

L’iscrizione è stata generalmente interpretata come “un caso di longevità degno di nota”. Si è ipotizzato che qui si faccia riferimento a un anno lunare di 30 giorni, o comunque a un ciclo diverso dall’anno solare; si è anche proposto che il numerale vada letto 52.

9 Plaster fragment whith inscription, incides or painted in red

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Teano, Santa Maria di Loreto (1793), from Pompeii according to Finati 1823

Inv. 2549 (Vetter 70)

“Audia (daughter of) Nimsius, 112 years old”.

This inscription is generally interpreted as “a remarkable case of longevity”, although it has been suggested that it could refer to a 30-day lunar year, or to some other cycle different from the solar year. The reading of the number as “52” has also been proposed.

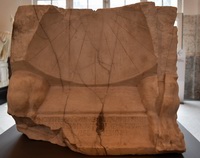

10 Blocco di architrave del colonnato circolare del pozzo del “Foro Triangolare”

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Tufo

II secolo a.C.

Pompei, cd. Foro Triangolare

Inv. 2551 (Vetter 15)

“Nimisio Trebio (figlio di) Trebio, magistrato della comunità curò la realizzazione”. Sulla terrazza all’estremità sudoccidentale del pianoro di Pompei sorge nel VI secolo a.C. il Tempio Dorico, un tempio di tipo etrusco ma con capitelli dorici, dedicato a Minerva. Il tempio, già restaurato nel IV secolo a.C., fu radicalmente ristrutturato secondo modelli ellenistici. Nel II secolo a.C. la terrazza fu cinta dal porticato dorico triangolare da cui discende il nome moderno di Foro Triangolare. In quell’occasione l’antico pozzo scavato nella lava fu preservato e monumentalizzato.

10 Fragment of a lintel from the circular colonnade surrounding the well of the “Triangular Forum”

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

2nd century BC.

Pompeii, Triangular Forum

Inv. 2551 (Vetter 15)

“Nimsius Trebius (son of) Trebius, public meddix, had (this) made”. The Doric Temple, a temple of Etruscan type, but with Doric capitals, dedicated to Minerva, was built in the 6th century BC on the terrace at the south-west extremity of the plain of Pompeii. The temple, already restored in the 4th century BC, was later radically restructured according to Hellenistic canons. In the 2nd century BC, this terrace was enclosed by a triangular Doric portico from which its modern name of Triangular Forum is derived. On that occasion, an ancient well dug into the lava was preserved and monumentalized.

11 Dedica di Vibio Popidio

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

II secolo a.C.

Pompei, via dell’Abbondanza, Casa VIII 3, 4 (1838)

Inv. 2543 (Vetter 13)

“Vibio Popidio (figlio di) Vibio, meddix pubblico questo portico fece sì che si facesse. Egli stesso approvò”.

Non si sa a quale portico si riferisce l’iscrizione. Il termine che indica l’edificio (passtata, riga 2) e un interessante grecismo: in greco, “portico” si dice pastas.

11 Dedication of Vibio Popidio

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

2nd century BC.

Pompeii, in Via dell’Abbondanza, Casa VIII 3, 4 (1838)

Inv. 2543 (Vetter 13)

“Vibius Popidius (son of) Vibius, public meddix, had this portico made. He approved it himself”.

The portico the inscription refers to has not been identified. It is called passtata (line 2), an interesting Grecism: in Greek, the name for “portico” is pastas.

12 Dedica del questore Spurio Maraio

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Travertino

II secolo a.C.

Pompei, Casa del Fauno (1831, 1841)

Inv. 2544 (Vetter 17)

“Spurio (figlio di) Ma(raio), questore, per delibera dell’assemblea fece sì che si facesse”.

12 Dedication of the quaestor Spurius Maraius

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Travertine

2nd century BC.

Pompeii, found in the House of the Faunus (1831,1841)

Inv. 2544 (Vetter 17)

“Spurius (son of) Ma(raius), quaestor, by decree of the assembly, had (this) made”.

13 Piccola ara

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Seconda metà del II secolo a.C.

Pompei, Casa del Fauno (1831)

Inv. 2550 (Vetter 21)

“A Flora”.

Flora è una delle divinità minori legate ai cicli rigenerativi della natura, il cui culto era diffuso nel mondo italico e si ritrova anche a Roma.

13 Small altar

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Second half of the 2nd century BC.

Pompeii, found in the House of the Faunus(1831)

Inv. 2550 (Vetter 21)

“To Flora”.

Flora is one of the minor deities connected to the regenerative cycles of nature. Her cult was diffused through the Italic world, and is attested in Rome as well.

14 Piccola base di statua

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Seconda metà II secolo a.C.

Pompei, Casa di Cornelio Rufo (1893)

Inv. 121758 (Vetter 16)

“Mazio Audio (figlio di) Cleppio e Decio Seppio (figlio di) Ofellio, questori, fecero”.

L’epigrafe è interessante perché riguarda la coppia dei questori, mentre altre riguardano compiti affidati a un solo questore su delibera dell’assemblea.

14 Small statue base

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Second half of the 2nd century BC.

Pompeii, found in the House of Cornelius Rufus (1893)

Inv. 121758 (Vetter 16)

“Mezius Audius (son of) Cleppius and Decius Seppius (son of) Ofellius, quaestors, made (this)”.

The epigraph is interesting as it concerns a pair of quaestors, while others only refer to tasks entrusted to a single quaestor by a decree of the assembly.

15 Frammento di base

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

II secolo a.C.

Pompei, Casa del Fauno (1865).

Inv. 2552 (Vetter 20)

“Vibio Satrio (figlio di) Vibio, edile”.

15 Base fragment

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

2nd century BC.

Pompeii, found in the House of the Faunus(1865)

Inv. 2552 (Vetter 20)

“Vibius Satrius (son of) Vibius, aedile”.

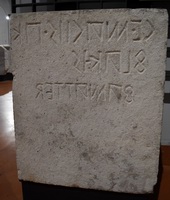

16 Il meddiss degetasius

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Metà II -inizi I secolo a.C.

Nola (Napoli)

Inv. 2539 (Vetter 115)

I due personaggi menzionati, Numerio Erennio figlio di Numerio e Percennio Gavio figlio di Percennio, sono investiti della carica di meddix degetasius, vale a dire di magistrato addetto alla riscossione delle decime.

Un altro magistrato con uguale carica compare nel testo del cippo abellano.

16 The meddiss degetasius

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Half of the 2nd - beginning of the 1rst century BC.

Nola (Napoli)

Inv. 2539 (Vetter 115)

The two persons mentioned, Numerius Herennius son of Numerius and Percennius Gavius son of Percennius, both held the office of meddix degetasius, i.e. a magistrate in charge of the collecting of the decimae. Another magistrate holding the same office is mentioned by the cippus from Abella.

17 Calco del Cippo Abellano

Calco del cippo in calcare scoperto nel 1745 dal padre G. Remondini come soglia di un edificio in cui erano stati reimpiegati materiali provenienti da Abella, ora conservato nel Seminario Arcivescovile di Nola.

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Fine II secolo a.C.

17 Cast of the Cippus from Abella

Cast of a cippus made of limestone discovered in 1745 by father G. Remondini, reused as the doorstep of a building in which materials from Abella had been re-employed, and presently kept in the archbishopric Seminar in Nola.

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

End of the 2nd century BC.

18 Blocco

Alfabeto osco. scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Metà II - inizi I secolo a.C.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano (Avellino),

località Cavuoto - S. Antonio (1930)

Inv. 144981 (Vetter 163)

Il testo è interessante per la presenza di un perfetto famatted= iussit, verbo che ricorre più frequentemente nella forma del presente faamat o faammant. Il dedicante dell’iscrizione era un componente della nobile famiglia dei Magi, gens di origine capuana di cui un illustre rappresentante, Decio Magio, si trasferì ad Aeclanum dando vita al ramo locale della famiglia.

18 Block

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Half of the 2nd- beginning of the 1st century BC.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano (Avellino), from Cavuoto - S. Antonio (1930)

Inv. 144981 (Vetter 163)

The text is interesting because of the presence of the perfect famatted=iussit, a verb that recurs more frequently in the present tense faamat o faammant. The dedicator of the inscription was a member of the noble family of the Magii, a gens of Capuan origin, an eminent member of whom, Decius Magius, moved to Aeclanum, where he founded a local branch of the family.

19 Blocco

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Metà II secolo a.C.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano (Avellino), contrada Torre Bosco - Ischitella (1930)

Inv. 145272 (Vetter 165)

È ricordato il dio Fatuvs, corrispondente al latino Fatuus, altro nome del dio Fauno. La presenza di un dio pastore risulta del tutto naturale nel pantheon di un popolo la cui economia doveva essere prevalentemente pastorale.

19 Block

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Half of the 2nd century BC.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano (Avellino), from Torre Bosco - Ischitella (1930)

Inv. 145272 (Vetter 165)

The text mentions the god Fatuvs, corresponding to the Latin Fatuus, another name of the god Faunus. The presence of a shepherd-god in the pantheon of this population, whose economy must have been essentially pastoral, is not surprising.

20 Piedistallo in forma di ara con dedica alla dea Mefite

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Metà II secolo a.C.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano (Avellino), località Cavuoto-S. Antonio (1930)

Inv. 250174 (Vetter 162)

“siviu magiu mefit”

Sevia Magia alla dea Mefite

La base sosteneva forse una statua di bronzo o di terracotta. La menzione della dea in una iscrizione in osco è un fatto piuttosto raro. Il nome della dedicante è in relazione con la famiglia dei Magi, già documentata nell’epigrafe precedente.

20 Pedestal in the form of an altar

Oscan alphabet, writing direction from right to left

Limestone

Half of the 2nd century BC.

Passo di Mirabella Eclano, at Cavuoto-S. Antonio (1930)

Inv. 250174 (Vetter 162)

“Sevia Magia to the goddess Mephitis”.

The inscription bears witness to the existence of a cult of Mephitis in ancient Aeclanum. The pedestal was probably for a statue of bronze or baked clay, judging from the characteristic shape of the recess for the insertion of a plinth. The goddess Mephitis rarely occurs in Oscan inscriptions. The woman dedicator must have belonged to the same family mentioned in the previous inscription, the Magi.

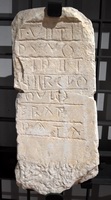

21 Architrave

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Travertino

175 a.C. circa

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), dal tempio A

Inv. 2524 (Vetter 151)

“Gneo Staio Stafidino figlio di Maras meddix tuticus ha dedicato” Il testo trasmette il nome del magistrato dedicante il tempio, che apparteneva alla famiglia degli Staii, ampiamente nota dalle iscrizioni osche di Pietrabbondante ma anche da quelle latine nell’area della tribù Voltinia e in altri centri dell’Italia meridionale. Grazie a questa documentazione e a quella offerta dalle fonti antiche è possibile ricostruire la storia di questa famiglia, protagonista delle vicende del Sannio, dal III fino al I secolo a C.

21 Architrave

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Travertine

Around 175 BC.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), from temple A

Inv. 2524 (Vetter 151)

“Cnaeus Staius Stafidinus, son of Maras, meddix tuticus dedicated”. The text commemorates the name of the magistrate dedicating the temple, who belonged to the family of the Staii well known from the Oscan inscriptions of Pietrabbondante, as well as the Latin ones found in the area of the Voltinia tribe and in the other centers of southern Italy.

Thanks to this evidence and to that of the ancient literary sources, it is possible to reconstruct the history of this family, that played an important role in the political events of the Samnium from 3rd to the 1st century BC.

22 Cornice di coronamento

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Travertino

175 a.C. circa

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), da tempio A

Inv. 2527 (Vetter 152)

Il dedicante appartiene alla famiglia degli Staii che, come è già stato detto, è ampiamente attestata nelle iscrizioni osche e latine da Pietrabbondante e appare strettamente legata alle diverse fasi monumentali del santuario.

22 Cornice

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Travertine

Around 175 BC.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), from temple A

Inv. 2527 (Vetter 152)

The dedicator belongs to the family of the Staii who, is frequently attested in the Oscan and Latin inscriptions of Pietrabbondante, and appears to have played an important role in the various monumental phases of the sanctuary.

23 Cippo

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Fine II secolo a.C.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), dal tempio A

Inv. 2529 (Vetter 149)

Il testo, incompleto e in parte non comprensibile, ricorda un personaggio di cui si è perduto il nome che, durante la meddicia di uno Staio figlio di Maras, in qualità di censore ( = keenstur) promosse degli interventi di restauro del tempio. Nel testo è di grande importanza la presenza della parola safinim, nome osco del Sannio che, in questa sede, allude chiaramente alla funzione politica e religiosa svolta dal santuario, all’epoca del suo piu intenso sviluppo edilizio, nell’ambito della touta, cioè della intera nazione dei Sanniti Pentri.

23 Cippus

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

End of the 2nd century BC.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), from temple A

Inv. 2529 (Vetter 149)

The text is incomplete and partially incomprehensible. It mentions a person (the name is lost), who during the meddicia of Statius, son of Maras, carried out, in his capacity of censor (keenstur), works of restoration in the temple. The presence in the text of the word safinim, the Oscan name of the Samnium, is of great importance, as it clearly alludes to the religious and political function of the sanctuary, at the time of its most intense building development, within the touta, i.e. the entire nation of the Pentrian Samnites.

24 Cippo

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Fine II - inizi I secolo a.C.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), dalla zona ad est del teatro

Inv. 2525 (Vetter 150)

Questa iscrizione era stata assunta dal Mommsen come elemento fondamentale per sostenere il riconoscimento di Bovianum Vetus in Pietrabbondante, poiché il testo veniva interpretato come la dedica, fatta dal meddix tuticus Novio Vesullio figlio di Trebio, di un tempio costruito a Boviano. L’interpretazione si basava sul significato attribuito al verbo aikdafed= costruì, che attualmente non e più accettata. Si ritiene, invece, che l’iscrizione si riferisca a qualcosa avvenuto a Boviano, forse la delibera della costruzione di un tempio nel santuario di Pietrabbondante, promossa dal magistrato Novio Vesullio.

24 Cippus

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

End of the 2nd - beginning of the 1st century BC.

Pietrabbondante (Isernia), from the area east of the theater

Inv. 2525 (Vetter 150)

This inscription was used by Mommsen as the main proof for his identification of Pietrabbondante with Bovianum Vetus, as the text was interpreted as a dedication by the meddix tuticus Novius Vesullius, son of Trebius, of a temple built of Bovianum. This interpretation was based on the translation of the verb aikdafed as “built”, no longer accepted today. The inscription is presently thought to refer, instead, to some other type of act, possibly a public resolution approving the construction of a temple in the sanctuary of Pietrabbondante, promoted by the magistrate Novius Vesullius.

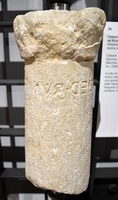

25 Colonnetta con dedica ad Ercole

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Agnone, località Le Macchie (Isernia)

Inv. 2528 (Vetter 148)

Il culto di Ercole si diffuse in territorio italico dalla Magna Grecia, e conobbe una grande diffusione testimoniata dalle attestazioni epigrafiche e dai frequenti rinvenimenti di statuine a carattere votivo che raffigurano il dio.

25 Column with dedication to Hercules

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Agnone, area of Le Macchie (Isernia)

Inv. 2528 (Vetter 148)

The text of the inscription is a dedication to the god Hercules, whose cult, imported from Great Greece, spread very early over the Italic territory, and enjoyed great popularity, attested both by epigraphs and by the finding of numerous votive statuettes representing the god.

26 Blocco

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Montalto di Rionero (Isernia)

Inv. 2531 (Vetter 142)

Il testo dell’epigrafe è una dedica, in relazione ad un edificio di cui non abbiamo notizia.

26 Block

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

Montalto di Rionero (Isernia)

Inv. 2531 (Vetter 142)

This text is a dedication referring to an unspecified public building.

27 Stele funeraria

Testo in dialetto paleosabellico e in alfabeto locale, scrittura con ductus serpentino

Arenaria

Fine VI secolo a.C.

Crecchio (Chieti), rinvenuta tra i resti di costruzioni romane (1846)

Inv. 2523

In base ad alcuni elementi il testo dell’epigrafe viene considerato di contenuto sacro ma la sua traduzione rimane molto problematica. Alcuni vocaboli sono riconducibili ai momenti di un rituafe, mentre la sequenza onomastica finale (Velaimes Staties) sembra interpretabile come una formula di sottoscrizione. Dalla parola ok[r]ikam = arce, deriva lo stesso toponimo moderno del luogo, Crecchio.

27 Sandstone slab

Text in paleosabellic dialect and in a local alphabet,the writing has a serpentine ductus

Sandstone

End of the 6th century BC.

Crecchio (Chieti), discovered among the remains of Roman buildings (1846)

Inv. 2523

On the basis of certain elements, this text is considered to be of sacred in content. Its translation is full of difficulties. Some words probably refer to the phases of a ritual, while the final onomastic sequence (Velaimes Staties) can be interpreted as a subscription formula. From the word ok[r]ikam = arche, derives the modern toponym of the place, Crecchio.

28 Stele

Testo in dialetto vestino e alfabeto latino. Scrittura da sinistra verso destra

Calcare

Fine III - metà II secolo a.C.

Navelli (L’Aquila), rinvenuta presso la chiesa di S. Maria in Cerulis

Inv. 2998 (Vetter 220)

Tito Vettio offre questo dono ad Ercole Giovio per la grazia data. La chiesa da cui proviene l’epigrafe sorge nell’area di un antico santuario che, secondo il testo della dedica, doveva essere dedicato ad Ercole Giovio.

28 Stele

Text in Vestine dialect; Latin alphabet. Written from left to right

Limestone

End of the 3rd - half of the 2nd century BC.

Navelli (L’Aquila), found near the Church of S. Maria in Cerulis

Inv. 2998 (Vetter 220)

Titus Vettius offer this gift to Hercules the Jovian for the grace granted. The church where this votive epigraph was found lies in the area of an ancient sanctuary which, on the evidence of the text, must have been dedicated to the cult of Hercules the Jovian.

29 Iscrizione funeraria

Testo in dialetto peligno; alfabeto latino

Calcare

Metà del I sec.a. C.

Corfinio (Aquila), dalla necropoli di Pentima (1877)

lnv. 247545 (Vetter 213)

Nonostante i numerosi tentativi di interpretazione il testo rimane oscuro in alcuni suoi passaggi. È possibile riconoscervi l’epitaffio per una sacerdotessa, Prima Petiedia, che giace essendosi compiuta la volontà del fato e, dopo aver trascorso la vita in ricchezza, è andata ora nel regno di Persefone. Il testo si conclude con il commiato ai lettori che recentemente è stato così tradotto: “Andate voi in letizia, benigni, ai quali piaccia aver letto questo. Vi dia ricchezza l’onesta Herentas” (Morandi). La dea Herentas era la Venere degli Italici, qui ricordata come Venere casta, in una forma di culto che nell’area corfinese era stato rivitalizzato da Silla come quello delta Venus Felix.

29 Funerary inscription

Text in Paelignan dialect; Latin alphabet

Limestone

Middle of the 1st century BC.

Corfinio (Aquila), from the necropolis of Pentima (1877)

Inv. 247545 (Vetter 213)

In spite of numerous attempts to interpret it, some of passages of the text still remain obscure. It is the epitaph of a priestess, Prima Petiedia, who lies to rest, according to the wish of Fate, and, having spent her life in wealth, is now gone to the reign of Persephone. The text is concluded with the farewell to the readers, which has recently been translated thus: “Go in happiness, oh kind ones whom it pleased to read this. Let honest Herentas give you wealth” (Morandi). The goddess Herentas was the Venus of the Italics, here appearing as the Chaste Venus. Silla revitalized this cult in the Corfianian are under the form of cult of Venus Felix.

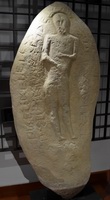

30 Stele

Testo in dialetto paleosabellico, iscritto a spirale intorno alla figura

Arenaria

Fine VI secolo a.C.

Bellante (Teramo) dall’alveo di un torrente (1867)

Inv. 111434

Stele funeraria che rappresenta il defunto nella posizione del “guerriero di Capestrano”. Il testo nella prima parte dà la localizzazione del sepolcro (tokam) di Tetis Alios, nella seconda una eventuale prescrizione per la sua tutela.

30 Stele

Text in paleosabellic dialect, written in a spirala round the figure

Sandstone

End of the 6th century BC.

Bellante (Teramo), from the bed of a creek (1867)

Inv. 111434

Funerary stele representing the deceased in the position of the “warrior from Capestrano”. The first part of the text gives the site of the burial (tokam) of Tetis Alios, the second part a prescription for his tutelage.

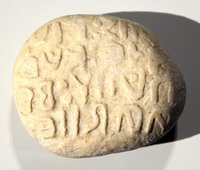

31 Ciottolo iscritto

Alfabeto osco

Calcare. 150-90 a.C.

Altilia (Saepinum).

Inv. 247546 (Vetter 161)

“Chi (sei) tu? Io sono una pietra. Di chi? Di Adius figlio di Aefinius”

31 Inscribed pebble

Oscan alphabet

Limestone. 150-90 BC

Altilia (Saepinum).

Inv. 247546 (Vetter 161)

“Who (are) you ? I am a rock. Whose? Adius son of Aefinius’s”

32 Frammento di lamina con dedica a una divinità

Testo opistografo, dialetto umbro e alfabeto etrusco

Bronzo. 300 a.C. ca.

Amelia-Terni (Ameria).

Inv. 2501 (Vetter 229)

Dedica a una divinità definita “Iovia”, forse da identificare con Marte.

32 Fragment of a lamina with a dedication to a deity

Opistographic text in the Umbrian dialect and the Etruscan alphabet

Bronze. Ca. 300 BC

Amelia-Terni (Ameria).

Inv. 2501 (Vetter 229)

Dedication to a deity characterized as “Iovia”, possibly to be identified with Mars.

33 Lamina con lex sacra

Testo e dialetto volsco; alfabeto latino

Bronzo. 300-275 a.C. ca.

Velletri-Roma. Dalla collezione Borgia

Inv. 2522 (Vetter 222)

Prescrizioni dei magistrati Egnatus Cossutius, figlio di Seppis e Marcus Tafanius, figlio di Gaius contro la violazione dei beni della divinità.

33 Lamina with lex sacra

Text in the Volscian dialect and Latin alphabet

Bronze. Ca. 300-275 BC.

Velletri-Rome From Borgia collection

Inv. 2522 (Vetter 222)

Measures inflicted by magistrates Egnatus Cossutius, son of Seppis, and Marcus Tafanius, son of Gaius for a violation of the premises of the goddess Declona.

34 Peso di stadera conformato a busto di Giove

Alfabeto osco

Bronzo. III secolo - inizi I secolo a.C.

Punta di Penne, Chieti (1846)

Inv. 2532 (Vetter 170)

“Di Giove Libero”

34 Scale weight in the shape of a bust of Jupiter

Oscan alphabet

Bronze. Third to early first century AD

Punta di Penne, Chieti (1846)

Inv. 2532 (Vetter 170)

”Of Jupiter Liber us”

35 Scodella di impasto bucchero ide

Due iscrizioni ad andamento destrorso graffite dopo la cottura: una, in lingua italica, all’esterno; l’altra, con caratteri affini al latino arcaico, entro la vasca Inizio V secolo a.C.

Latina, Santuario della dea Marica alla foce del Garigliano.

Inv. 266166 (Rix Ps 10)

Parte esterna:

“di Afidio o Audio”

Parte interna:

“Procacciati a me. Io sono con i miei soci di Trivia (o per Trivia) degli dei la buona [‘-]nei”

Oppure

“Sono con i miei soci appartenente a Trivia. Due degli dei. Non ti impossessare di me”

35 Buccheroid impasto bowl

Two inscriptions running from left to right, one in an Italic language, on the outside, the other in similar letters to archaic Latin, inside the vase

Early 5th century BC.

Latina, sanctuary of the goddess Marica at the mouth of the Garigliano river.

Inv. 266166 (Rix Ps 10)

Outside:

“of Afidius or Audius”

Inside:

“Provided for me. I am with my associates of Trivia (or for Trivia) of the gods the good […] in the”

Or

“I am with my associates belonging to Trivia. Two of the gods. Do not possess

me”

36 Kylix attica a vernice nera (forma Agorà 469)

Testo in lingua osca e in alfabeto etrusco

Metà V secolo a.C.

Nola, (scavi Raffaele Barone 1859).

lnv. 80554 (Vetter 117)

“Sono di Lucio Nevio”

36 Black-paint Attic kylix (shape Agora 469)

Text in the Oscan language and the Etruscan alphabet

Mid 5th century BC

Nola, (Raffaele Barone excavations, 1859).

Inv. 80554 (Vetter 117)

“I am of Lucius Nevius”

37 Kylix di tipo attico

Testo in alfabeto etrusco e in lingua di incerta definizione tra etrusca e sabellica

Prima metà V secolo a.C.

Nola, (scavi Raffaele Barone 1859)

Inv. 80557 (Vetter 120)

“Tec. liiam”

37 Attic-type kylix

Text in the Etruscan alphabet; the language is either Etruscan or Sabellic

First half of the 5th century BC

Nola, (Raffaele Barone excavations, 1859)

Inv. 80557 (Vetter 120)

“Tec. liiam”

38 Coppa a vernice nera “capuana” con stampigliature all’interno della vasca

Testo in lingua e alfabeto osco

Fine del IV secolo a.C.

Sant’Agata dei Goti (Saticula), 1804

Inv. 80561 (Vetter 125)

“Patera di Maraio Ponzio”

38 Black-paint “Capuan” cup with stamps on the inside

Text in the Oscan language and alphabet

Late 4th century BC.

Sant’Agata dei Goti (Saticula), 1804

Inv. 80561 (Vetter 125)

“Patera of Maraius Pontius”

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis