Indice dei Musei

presenti in miti3000

Napoli Museo Nazionale - Piano - 1 - Sezione Epigrafi

Testo

MANN - Piano meno uno - Sezione Epigrafi

Sala CLI

NEAPOLIS

I coloni euboici, che nell’VIII secolo a.C. si insediarono prima a Ischia e poi a Cuma, nel secolo successivo crearono un avamposto in quello che sarà poi il territorio di Napoli. Questo insediamento, che occupava il colle di Pizzofalcone e l’isoletta di Megaride (Castel dell’Ovo), nelle fonti è noto come Partenope o Palepoli. Il secondo nome indica “la città vecchia” contrapposta a Neapolis “la città nuova”. Questa fu fondata alla fine del VI secolo, in un area più interna, corrispondente all’attuale centro antico di Napoli.

La grecità di Napoli continuò a sopravvivere nonostante la pressione militare prima dei Campani e poi dei Romani. Nel IV secolo a.C. alcuni Campani furono accolti come cittadini e della loro presenza sono prova i numerosi nomi di origine osca attestati nelle fonti letterarie ed epigrafiche.

Ben più complessi e gravidi di conseguenze furono i rapporti con Roma. Nel 326 a.C. fu stipulata la prima alleanza, che lasciò alla città la sua autonomia amministrativa. Ma nel 90 a.C. Napoli si trovò a dover accettare la cittadinanza romana, assumendo lo status di municipio. Iniziò così per la città un periodo di decadenza economica, che la privò del ruolo fino ad allora svolto nel Mediterraneo. La sua identità restò affidata alla difesa della cultura e della lingua greca, il cui uso si protrasse almeno fino al III secolo d.C..

A testimonianza di ciò abbiamo più di 250 iscrizioni greche, a volte note solo attraverso i disegni e le notizie tramandate dagli studiosi del passato. Di quelle superstiti la maggior parte è in questo museo, altre sono conservate nelle strade e nelle chiese del centro antico. Il caso ha fatto in modo di cancellare quasi totalmente le testimonianze di età classica ed ellenistica e di preservare, invece, i testi di età imperiale.

Neapolis

The Euboean colonists who, in the course of 8th century BC, settled first in Ischia and then in Cumae, in the following century created an outpost on the territory of the future city of Neapolis. This early settlement, on the hill of Pizzofalcone and the islet of Megaris (Castel dell’Ovo), in the ancient sources is known as Parthenope or Palaepolis. This latter name means “old city”, as opposed to Neapolis, the “new city”. Neapolis was founded at the end of the VI century BC, in a more inland area corresponding to the present-day ancient center of Naples. The city’s Greek identity was strong in spite of the military pressure of the Campanians first and then of the Romans. The former were almost immediately accepted as citizens by full right and their presence is proven by the many names of Oscan origin attested in the literary and epigraphic sources.

Relations with Rome were, instead, much more complex and momentous. In 326 BC, Neapolis and Rome entered into their first alliance, which left to the former city its administrative autonomy. It was only in 90 BC that Neapolis was constrained to accept Roman citizenship, assuming the status of a municipium. In those years, the city went through a period of economic decline, losing the preeminent role it had enjoyed until then. It managed, nevertheless, to preserve its identity through a strenuous defence of its Greek linguistic and cultural heritage. Greek continued to be used at least until the 3rd century BC. Infact, as a proof, we have more than 250 Neapolitan Greek inscriptions well preserved. Most of these epigraphs are known only through the drawings and indications handed down by scholars of the past centuries. Of those that remain, most are kept in this museum, while a certain number is still dispersed in the streets and churches of the ancient city.

By some quirk of fate, the documents of Classical and Hellenistic age have been almost totally destroyed, while the preserved texts being nearly all of the Imperial age.

Neapolis, le istituzioni politiche

Come ogni città greca anche Neapolis aveva un consiglio (boulè o synkletos) e un assemblea popolare (demos o ekklesia). Dal 90 a. C. la boulè costituì il consiglio municipale; l’ekklesia è citata in epigrafi di età imperiale nella formula ordo populusque Neapolitanus. Il magistrato supremo era in origine il demarco. Forse già nel IV secolo a.C. alcune funzioni furono assunte dagli arconti, citati a Cos in un decreto del 242 a.C. Le due cariche sopravvissero fino ad età imperiale: gli arconti continuarono a svolgere un ruolo rilevante; il demarco ebbe una funzione onoraria. Dalle iscrizioni sono noti: i magistrati che sovrintendevano al mercato (agoranomoi), e alle attività sportive (gymnasiarchoi e agonothetai); i segretari pubblici (grammateis e scribae) e i laucelarchi, di cui non è possibile stabilire la funzione.

Nel II secolo d.C., o all’inizio del III, la città divenne colonia. La creazione nel IV secolo d.C. di un governatore della Campania con sede a Capua determinò la sua decadenza politica.

Istituzione tipicamente greca, attestata a Napoli dalla fondazione fino all’impero, è quella delle fratrie, associazioni cui spettavano, almeno in origine, funzioni di controllo sui diritti civili e le tradizioni religiose. Esse possedevano sedi per le loro attività, praticavano culti propri e disponevano anche di sepolture riservate. I loro nomi sono quasi tutti collegati ai miti e ai culti dei coloni euboici: Aristei, Artemisi, Cretondi, Cumei, Ermei, Eubei, Euereidi, Eumelidi, Eunostidi, Panclidi, Teotadi. A questi si aggiunge un nome lacunoso (forse Eraclidi) e gli Antinoiti, così detti in onore di Antinoo, favorito dell’imperatore Adriano e affiliati forse agli Eunostidi.

Neapolis political institutions

Like every Greek city, Neapolis had a council (boulé or synkletos) and a citizen assembly (demos or ekklesia).The council or boulè took on the functions of a municipal council, while the assembly or ekklesia is cited in epigraphs of imperial period as ordo populusque Neapolitanus. The supreme magistrate was originally the demarchos. Possibly as early as the 4th century BC, his functions were assumed by the archons, who are mentioned in an official decree of 242 BC found in Cos. Both offices continued to exist in the Imperial age but, while the archons continued to have an important role, the title of demarchos became purely honorary. From the inscriptions we learn of magistrates presiding over the marketplace (agoranomoi), as well as public scribes (grammateis and scribae) and overseers of sports (gymnasiarchoi and agonothetai). In the 2nd century, or at the AD beginning of the 3rd, the city was given the status of colony, but it was only the installing, in the 4th century AD., of a governor of Campania, with his seat in Capua, that caused its political decline. Another typically Greek institution, which survived in Neapolis from its foundation to the Imperial age, is that of the phratries, that is associations with original functions of supervision and control in questions related to civil jurisdiction or religious traditions.They owned seats for their activities, practised their own cult and had reserved tombs. Almost all their names go back to the myths and cults of the Euboean colonists: Aristeioi, Artemisioi, Chretondes, Cymaioi, Hermeioi, Euboeioi, Euereides, Eumelides, Eunostides, Pancleides, Theotades. To these we must add a doubtful name (possibly the Heraclides) and the Antinoites, so called in honour of Antinoos, emperor Hadrians favourite, and possibly affiliated to the Eunostides.

Neapolis - culti e concorsi sportivi

L’antico culto della sirena Partenope si lega al nome del primo insediamento e ad una tradizione diffusa nel mondo greco. Ancora in età imperiale si venerava la presunta tomba della Sirena, il cui cadavere, secondo la leggenda, sarebbe stato portato dal mare sul litorale di Napoli. Le divinità principali erano Apollo, Demetra e i Dioscuri. Del primo, che guidò in Occidente i coloni euboici, parla il poeta Stazio, citandolo tra gli dei patri. Il tempio sull’acropoli (largo S. Aniello a Caponapoli) è considerato pertinente al culto di Demetra, per la quale esisteva un sacerdozio femminile. I Dioscuri, infine, erano titolari del grande tempio del Foro, sui cui resti sorse poi la chiesa di S. Paolo Maggiore. Le iscrizioni menzionano altre divinità greche: Afrodite, Aristeo, Artemide, Asclepio e Igea, Atena Sicula, Dioniso (detto Hebon ‘Giovanetto’), Eracle, Ermes, Leucotea, e la Tyche ‘Fortuna’ di Neapolis. A queste si aggiungono il fiume Sebeto, la dea Nemesi e tre divinità orientali (Giove Dolicheno, Iside e Mitra). Particolare rilievo ebbe la venerazione per l’imperatore Augusto. In suo onore nel 2 d.C. furono istituiti un sacerdozio e una festa religiosa, collegata al concorso internazionale degli Italikà Rhomaia Sebastà Isolympia. Ai testi presenti nel Museo si aggiungono le nuove iscrizioni scoperte nel 2003 in piazza Nicola Amore, durante i lavori per la Linea 1 della metropolitana. Il sito ha restituito il tempio del culto imperiale e un portico che apparteneva, quasi certamente, a uno dei ginnasi di Napoli. Le lastre che ne rivestivano la parete interna recano i nomi di quanti vinsero i Sebastà nelle edizioni del 74, 78, 82, 86, 90, 94 d.C. Le vittorie riguardano gare atletiche, ippiche e artistiche, ripartite fra competizioni retoriche, poetiche, musicali e teatrali.

Neapolis Cults and sport games

The ancient cult of the siren Parthenope is connected to the name of the first settlement, and goes back to a widespread Greek tradition. In the Imperial age, there still existed a cult of the alleged tomb of the siren. Her corpse, according to tradition, was carried by the waves onto the shore of Naples. The main deities of the city were Apollo, Demeter and the Dioscuri. The former led the Euboean colonists to the West, and is mentioned by the poet Statius as one of the town gods. To Demeter was dedicated the temple on the acropolis (largo S. Aniello a Caponapoli) and a female priesthood. To the Dioscuri, instead, was dedicated the great temple of the forum, on whose remains the church of S. Paolo Maggiore was later erected.

The epigraphic sources also attest the presence of numerous Greek cults, such as Aphrodite, Aristaeus, Artemis, Asclepius and Aegia, Athena Sicula, Dionysus (named Hebon the youth), Heracles, Hermes, Leucothea and Tyche “Fortuna” of Neapolis. Moreover the river Sebetos and the goddess Nemesis were also adored and finally three more oriental gods (Jupiter Dolichenos, Isis and Mithras). Besides the cult of the emperor Augustus was especially relevant. In his honour, in the year 2 AD, it was established a priesthood and a religious festival. Linked to the the festival it was held an international competition of Italikà Rhomaia Sebastà Isolympia.

To the texts present in this museum we have to add the new inscriptions discovered in 2003, in piazza Nicola Amore, during the excavations for the underground Linea 1. This site has given back a temple of the imperial cult and a porch, almost certainly, part of one of the gymnasi a of Neapolis. On the marble tiles covering the inner walls we can read the names of the winners (artists and athletes) of the Sebastà in the years 74, 78, 82, 86, 90, 94 AD. The victories relate to athletic as well as equestrian and artistic competitions, the latter divided in rhetorical, poetical, musical and theatrical.

L’Epigrafia italica

L’italico è una lingua indoeuropea, al pari del greco e del latino, che si distingue in dialetti in base a lessico grammatica, fonetica, alfabeto.

Le iscrizioni vanno dal VII/VI secolo al 1 secolo a.C e provengono dall’Italia centromeridionale e da alcuni centri della Sicilia. I1 gruppo più antico è quello delle epigrafi paleosabelliche in alfabeto locale con influenze etrusche attestate nelle Marche meridionali, nell’Abruzzo settentrionale e nella valle del Tevere, in area sabina. A nord di questa c’è l’area umbra. L’umbro è affine alla lingua delle iscrizioni paleosabelliche, ma adotta l’alfabeto etrusco “riformato”.

A sud, tra VI e V secolo emerge un’area linguistica e culturale completamente autonoma: l’area sannita, corrispondente al Molise e alla Campania, dove i Sanniti ebbero i loro primi insediamenti e la loro prima espansione. Fu questa la culla dell’altra grande lingua italica: l’osco, che nell’arca sannita adotta anch’esso un alfabeto nazionale modellato su quello degli Etruschi nella forma elaborata in Campania. L’osco si diffuse in Basilicata e Calabria per successive ondate di espansione sannita di V/IV secolo a.C. I Sanniti spintisi a sud si chiamarono Lucani e Bretti e subirono l’influsso delle colonie greche, da cui presero il modello per il loro alfabeto.

Completano il quadro i dialetti “italici minori” o “nord-sabellici”, linguisticamente non uniformi, con carattere ora umbro, ora osco, attestati da epigrafi che vanno dal IV al I secolo a.C., in alfabeto latino, segno di avanzata romanizzazione. È possibile che questi dialetti, in cui riaffiorano elementi sabini, riflettano la frantumazione dell’ethnos sabino, che dovette ESSERE definitiva nel V secolo a.C.

Italic epigraphy

Italic is an Indo-European language, like Greek and Latin, which is divided in dialects on the ground of vocabulary, grammar, phonetics and alphabet. Inscriptions must be dated from the 7th 6th century to the 1st century BC coming from Central and Southern Italv and from some areas in Sicily. The group of the Proto-Sabellic epigraphs is the oldest one, written in the local alphabet with Etruscan influences attested in Southern Marche, Northern Abruzzo and the Tiber valley in the Sabine area. North of it is the Umbrian area. Umbrian is similar to the language of the Proto-Sabellic inscriptions but adopting the “reformed” Etruscan alphabet.

Southward, between the 6th and the 5th century a completely autonomous linguistic and cultural area emerges: the Samnite area, corresponding to Molise and Campania, where the Samnites first settled and expanded. This was the cradle of the other great Italic language: Oscan, which in this area also adopts a national alphabet modelled on the Etruscan one in the form drawn up in Campania. Oscan spread over Basilicata and Calabria by successive waves of expansion of the Samnites in the 5th and 4th century BC. The Samnites that moved to the South were called Lucani and Bretii and were influenced by the Greek colonies, from which they took the model for their alphabet.

To complete the picture “minor Italic” dialects or the “nord-sabellic” must be mentioned, linguistically non-uniform, sometimes with Umbrian or Oscan features, attested by inscriptions ranging from the 4th to the 1st century BC, in the Latin alphabet, a sign of advanced Romanization. It is possible that these dialects, in which some Sabine elements are present, reflect the final crushing of the Sabine ethnos, which definitely took place in the 5th century BC.

Capua

Le origini dell’etrusca Capua risalgono al IX sec. a.C., ma è solo a partire dal VI sec. a.C. che è percepibile la sua fisionomia urbana. L’elemento etrusco entra in crisi nel V sec. a. C. quando la componente indigena di matrice osco-sannita, già ammessa in città in condizioni subalterne, nel 438 a.C. forma una comunità (touto in osco) col nome di Campani e pochi anni dopo prende sanguinosamente il potere prima a Capua e poi a Cuma. La nuova Capua vanta un aristocrazia di cavalieri (equites campani), famosi come comandanti di milizie mercenarie al servizio di Greci d’Italia e di Sicilia, Cartaginesi, Etruschi, e spesso inclini ad autonome operazioni di conquista. La pressione sulla pianura campana dei Sanniti dell’Appennino, induce i Campani ad allearsi con Roma, che incorpora Capua e il suo territorio nello stato romano attribuendole la “cittadinanza senza diritto di voto” (civitas sine suffragio). Durante la seconda guerra punica la città si schiera con Annibale; riconquistata nel 211 a.C., subisce la confisca totale del territorio e l’annullamento della personalità giuridica della comunità fino al I sec. a.C.

Le iscrizioni in osco provengono dalle necropoli e dall’antichissimo santuario extraurbano del fondo Patturelli. Si tratta per lo più di “iovile” (IV-III sec. a.C.), chiamate così per la frequenza del termine iúvilas o diuvilas, che indica qualcosa di materiale non ben identificabile. I testi incisi su stele di pietra o terracotta riportano le prescrizioni per rendere sacre le iúvilas con sacrifici officiati alla presenza di un magistrato cittadino, in precise scadenze del calendario. All’epoca delle “iovile” Capua era amministrata da un collegio di magistrati (meddices) al cui vertice stava il magistrato della comunità (meddix tuticus).

Capua

The origins of the Etruscan Capua go back to the 9th century BC,but it’s only from the 6th century BC that it’s clear its urban characteristic. The etruscan identity failed in the 5th century when the indigenous Oscan-Samnite population, formely subjugated, in 438 BC formed a touto (in oscan “community”) named Campani and, few years later, bloodily took power first in Capua and afterwards in Cumae. The new Capua was ruled by a horse-riding aristocracy (equites campani), already famous as commanders of mercenary troops in the service of the Greeks of Italy and Sicily, of the Carthaginians and of the Etruscans, and often inclined to personal expeditions of conquest. The pressure of the Appenninic Samnites on the Campanian plain induced the Campanians to turn to Rome for help. By supporting the aristocracy Roma was able to incorporate Campania into the Roman state granting its inhabitants the “citizenship withhout the right to vote”.

During the second Punic War, Capua was in favour of Hannibal but, when the Roman reconquered the city in 211 BC, it was punished by the total confiscation of its territory and the cancelling of its political rights.

The necropolises and the very ancient extraurban sanctuary of the Patturelli plot have yielded the most important corpus of Oscan epigraphs from Capua. Among these are the iuvilae (4th and the 3th century BC) so named from the recurring of the term iúvilas or diuvilas, which indicates a material object. The texts, enscribed on stone and clay steles, contain the prescriptions for the consecration of the iúvilas with sacrifices celebrated in the presence of a town magistrate on specific dates. At the time of the iuvilae Capua was administered by a board of meddices (magistrates) led by a meddix tuticus (magistrate of the touto, the community).

Cuma

Cuma fu fondata dai greci provenienti dall’isola di Eubea attorno alla metà dell’VIII sec. a.C. Nel VII-VI sec. a.C. la colonia arrivò a dominare il golfo di Napoli. Alla fine del VI, dopo aver sconfitto Umbri e Etruschi (524 a.C.), difese i Latini minacciati dall’etrusco Porsenna (505 a.C.). Conobbe poi la tirannide di Aristodemo, appoggiata dal popolo contro gli oligarchi esiliati presso l’etrusca Capua. La riconquista del potere da parte degli oligarchi, la vittoria navale di Cuma contro gli Etruschi nel 474 a.C., e la fondazione di Neapolis, celano la dipendenza della città da Siracusa, e una debolezza interna, di cui approfitteranno i Campani per conquistarla nel 421 a.C. Nel 340, minacciati dai Sanniti della montagna, i Campani si dettero a Roma, ricevendone la “cittadinanza senza diritto di voto” e, più tardi (180 a.C.), l’autorizzazione a usare il latino in taluni atti pubblici. Da Cuma proviene l’unica attestazione (nn. 26-27) di due organi politico-amministrativi, citati con le sigle m.v. e m.X; “m” è abbreviazione di meddix (= magistrato, in osco); “m.v.” meddiss vereias (magistrato della vereia). La vereia era un istituzione di tipo militare impiegata a volte in spedizioni mercenarie. Si è notato che una realtà del genere si sarebbe mal conciliata con l’inclusione di Cuma nello stato romano, e si è ipotizzato che nel III e II secolo a.C. fosse divenuta un’associazione con fini di pubblica utilità, posta sotto il controllo delle autorità. Lo scioglimento della sigla m.X è più problematico: X è il numerale “dieci”, che secondo alcuni significherebbe meddices decem (collegio di 10 magistrati associati al meddiss vereias), secondo altri meddiss degetasis, il magistrato incaricato delle decime, cioè delle percentuali di raccolto prelevate a fini fiscali.

Cumae

Cumae was founded by Greeks coming from the island of Euboea around 750 BC. In the 7th - 6th century BC the colony dominated the Bay of Naples. At the end of the 6th century BC, after having vanquished Umbrians and Etruscan (524 BC), it successfully went to the rescue of the Latins, threatened by the Etruscan Porsenna (505 BC). Afterwards it experienced a period under the tyrant Aristodemus supported by the people against the oligarchs, who had gone in exile to the Etruscan town of Capua.

The reconquering of power by the oligarchs, the naval victory of Cumaeans against the Etruscans in 474 BC and the foundation of the colony of Neapolis, actually belies the city’s dependence from Syracusae, and its internal weakness, of which the Campanians took advance to conquer Cuma in 421 BC. In 340 BC threatened by the Samnites of the mountains, the Campanians gave themselves over to Rome, from which they received the “citizenship without the right to vote” and, later on (180 BC), the authorization to use Latin for certain public documents.

Only in Cuma, we know from the inscriptions (nn. 26-27) the existence of two political-administrative organs, indicated by the initials “M.V.” and “M. X”: “M” is an abbreviation of meddiss (Oscan for “magistrate”); “M.V.” presumably means meddiss vereias (magistrate of the vereia). The vereia was a town institution of a military type and sometimes employed for mercenary expeditions. It has been observed that such an institution could have posed obstacles to the incorporation of Cumae into the Roman state, and it has been suggested that,between the 3th and 2th century BC, the vereia became an association with public good purposes, placed under the control of the authorities.

The interpretation of the initials “M. X”. is more problematic. It is beyond doubt that “X”is the numeral “ten” but, according to some, it means meddices decem (i.e. board of 10 magistrates associated to the meddiss vereias), while others think it designates the meddiss degetasis, a magistrate whose task it was to collect the decimae, i.e. the quota of the harvest collected as tax.

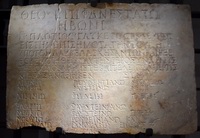

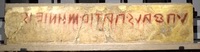

1 Architrave con dedica votiva

Marmo

I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli

Inv. 2447. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia.Napoli, I, n. 11

“I Teotadai (dedicarono) agli dei Augusti e agli dei della fratria”.

1 Lintel bearing a votive dedication

Marble

1st-2nd century AD.

Naples

Inv. 2447. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 11

“The Theotadai (dedicated) to the Augustan gods and to the gods of the phratry”.

2 Decreto della fratria degli Artemisi

Marmo

194 d.C.

Casoria, contrada Carbonella

Inv. 250165. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 44

Dopo la menzione dei consoli romani e del demarco il decreto ricorda le numerose benemerenze di Munazio Ilariano, il quale “… vedendo che la nostra fratria era disadorna e antiquata, con una decisione nobile e magnanima abbellì la sede con marmi variopinti, i piu belli e rari per sontuosità di allestimento, e fece il tetto d’oro senza risparmio alcuno nel dispendio di ricchezze e nelle spese destinate a ciò, e allestì per i fratri Artemisi una sala da pranzo più bella delle altre e costruì un tempio per la dea Artemide, da cui la fratria prende il nome, degno della dea e della comune pietà…”.

A seguito di tanta generosità gli Artemisi decretano per Munazio Ilariano e per suo figlio Mario Vero l’erezione di due statue ciascuno e la dedica di ritratti su scudi d’oro. A tutto ciò viene aggiunto il dono di 50 chorai, da intendere probabilmente come particelle di terreno. Al decreto fa seguito, in greco e latino, la risposta di Munazio Ilariano, il quale, nel ringraziare la fratria, rifiuta con modestia gran parte degli onori concessi.

2 Decree of the phratry of the Artemisioi

Marble

194 AD.

Casoria, area of Carbonella

Inv. 250165. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 44

After mentioning the names of the Roman consuls and of the demarchos, the decree commemorates the numerous merits of Munatius Hilarianus, who “… seeing that our phratry was unadorned and antiquated, by noble and magnanimous decision embellished its seat with multicoloured marbles, the most beautiful and rare in sumptuousness and arrangement, and made the roof of gold, without managing his wealth and expenses for this, and arranged for the Artemisioi a dining room more beautiful than the others, and built a temple for the goddess Artemis - from whom the phratry takes its name - worthy of the goddess and of common piety…”.

In gratitude for such generosity, the Artemisioi decreed the erection for Munatius Hilarianus and his son Marius Verus of two statues each, and the dedication of portraits on golden shields. To all this was added a gift of 50 chorai, probably plots of land. The decree is followed by Munatius Hilarianus’ answer, in Greek and Latin, in which, while thanking the phratry, he modestly refuses most of the honors.

3 Fondazione testamentaria a favore della fratria degli Aristei e di Valeria Musa, vedova del benefattore

Marmo

Fine I secolo a.C. - inizio I secolo d.C.

Napoli

Inv. 2446. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 43

Lato A

La fratria è tenuta a celebrare sacrifici e banchetti in giorni prestabiliti e a fornire prestiti in denaro ai privati e alla città. Si legge (linee 15-20):” … coloro che hanno ricevuto il prestito versino il denaro il giorno 7 del mese Panteone nell’assemblea in seduta plenaria e la fratria decreti a chi desidera fare il prestito e così dunque avvenga una nuova operazione ogni anno. In questi due giorni, in cui si fanno i sacrifici e il banchetto, a Valeria Musa venga versato il dovuto”.

Lato B - Alcune lettere latine.

3 Testamentary foundation in favour of the phratry of the Aristaioi and of Valeria Musa, widow of the benefactor

Marble

End of the 1st century BC - beginning of the 1st century AD.

Naples

Inv. 2446. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 43

Side A

The phratry is required to celebrate sacrifices and banquets on fixed days, and to lend money to private citizens and to the city. At lines 15-20, we read: “… let those who have borrowed give back the money on day 7 of the month of Pantheon in the assembly gathered in plenary séance, and let the phratry decree to whom it wishes to lend, and thus let a new operation take place each year. During these two days, in which the sacrifices and the banquet are celebrated, let her due be given to Valeria Musa”.

Side B - Some Latin letters.

4 Dedica alle divinità della fratria dei Cumei

Base cilindrica su plinto quadrangolare decorato con motivi a rilievo

Marmo

Inizio II secolo d.C.

Sulla base, destinata a reggere un vaso di kg. 18,5, sono raffigurati al centro Dioniso, a destra Efesto e a sinistra una divinità irriconoscibile (forse Eracle).

Napoli

Inv. 2448. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 9.

“Marco Cocceio Cal (…), liberto dell’imperatore, con i propri figli Tizio Aquilino e Flavio Crescente (dedicò) un vaso di 56 libbre e 4 once e mezza agli dei fratri dei Cumei”.

4 Dedication to the gods on the part of the phratry of the Cymaioi

Cylindrical base on square plinth bearing a decoration in relief

Marble

Beginning of th 2nd century AD.

On the base, made to support a vase weighing 18,5 kilograms, are represented Dionysus in the middle, Hephaestus on the right and, on the left, an unrecognizable deity (possibly Hercules).

Naples

Inv. 2448. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 9.

“Marcus Cocceius Cal(…), libertus of the emperor, with his sons Titius Aquilinus and Flavius Crescens (dedicated) a vase of 56 pounds and 4 ounces and a half to the phretores gods of the Cymaioi”.

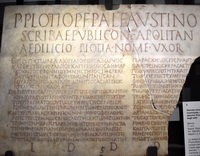

5 Decreto emanato dal consiglio municipale, per tributare onori al defunto Plozio Faustino, segretario degli edili

Marmo

71 d.C.

Napoli, Rione Duchesca

Inv. 250163.

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli I, n. 84

La dedica in latino è posta dalla moglie Plozia Nome. Dopo la menzione dei consoli romani e dei magistrati cittadini il testo espone le motivazioni del decreto:

”… per simpatia e per la memoria, dovuta a coloro che hanno vissuto nobilmente, della stima da parte dei vivi, la quale sola consolazione e di conforto nell’ultimo giorno, soprattutto quando qualcuno insieme alla mitezza dei modi abbia mostrato anche, per quanto è possibile, zelo verso la patria, come appunto Plozio Faustino…”.

Il decreto si conclude con la disposizione di offrire 10 libbre di incenso e un terreno per la sepoltura.

5 Decree emitted by the municipal council to tribute honors to the deceased Plotius Faustinus, secretary of the aediles

Marble

71 AD.

Napoli, Rione Duchesca

Inv. 250163.

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 84

The dedication in Latin is placed by his wife Plotia Nome. After mentioning the Roman consuls and the city magistrates, the text expounds the reasons for the decree:

“… as a token of sympathy and as memory, due to those who have lived nobly, of the esteem on the part of the living, which is the only comfort on the last day, especially when someone has showed both mildness of manners and, as much as possible, zeal towards his home town, just as Plotius Faustinus…”.

The decree is concluded by a resolution to offer 10 pounds of incense and ground for the burial.

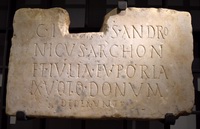

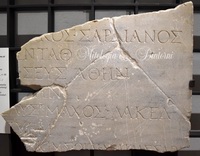

6 Dedica votiva dell’arconte Giulio Andronico

Marmo

Fine II secolo d.C. - prima meta III secolo d.C.

Napoli, via S. Sebastiano

Inv. 250164

Inscriptiones latinae selectee, n. 6453

“Caio Giulio Andronico arconte e Giulia Euporia offrirono in dono secondo il voto”.

6 Votive dedication by the archon Julius Andronicus

Marble

End of the 2nd century AD - first half of the 3rd century AD.

Naples, via S. Sebastiano.

Inv. 250164

Inscriptiones latinae selectee, n. 6453

“Caius Julius Andronicus, archon, and Julia Euporia offered according to their vow”.

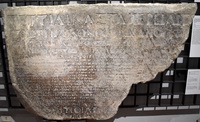

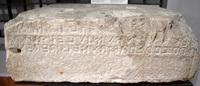

7 Tre decreti emanati dal consiglio municipale, per tributare onori alla defunta Tettia Casta, sacerdotessa di un culto femminile (forse Demetra)

Marmo

71 d.C.

Napoli, via Egiziaca a Forcella

Inv. 2452

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 85

Nel primo decreto, si legge (linee 7-11):

“… convenendo sull’opinione di tutti che sia un dolore comune la morte precoce di Tettia Casta, donna che ha aspirato ardentemente al rispetto verso tutti ed all’amore verso la patria e che ha innalzato incessantemente statue d’argento agli dei per beneficare nobilmente la città, (piacque) di onorare Tettia Casta con una statua e un ritratto su scudo e seppellirla a spese pubbliche, ma a cura dei parenti, che è difficile confortare, e offrire tot libbre di incenso e un luogo per la sepoltura e pagare per queste cose…”

I successivi decreti aggiungono altri onori e determinano l’estensione del terreno concesso per la sepoltura.

7 Three decrees issued by the municipal council, establishing honors to be conferred to the deceased Tettia Casta, priestess of a feminine cult (possibly Demeter)

Marble

71 AD.

Naples, via Egiziaca a Forcella

Inv.2452

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 85

In the first decree we read (fines 7-11):

“… agreeing with the opinion of all that the premature death of Tettia Casta is a common grief, she being a woman who ardently aspired to express her respect of all and her love of her home town, and who incessantly erected silver statues to the gods to nobly benefit the city, (so it pleased the city) to honor Tettia Casta with a statue and a portrait on a shield, and to have her buried at public expense, but by her relatives, whom it is hard to comfort, and to offer x pounds of incense and a place for the burial and to pay for these things…”.

The other two decrees add further honors and establish the extension of the ground allotted for the burial.

8 Dedica posta al dio Hebon da Publio Plozio Glicero e da altri affiliati del culto

Marmo

II-III secolo d.C.

Napoli

Inv. 2449

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 4

Dopo il nome del dio si legge (linee 3-8):

“… Publio Plozio Glicero, eletto nel distintissimo consiglio dagli ex laucelarchi e iniziato secondo le consuetudini nel mistero di questo sacerdozio, essendosi perfezionato in modo completo e totale, dedicò”.

Seguono i nomi degli altri fedeli.

8 Dedication placed to the god Hebon by Publius Plotius Glycerus and by other affiliates of the cult

Marble

2nd-3rd century AD.

Naples

Inv. 2449

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 4

After the name of the god, we read (lines 3-8):

“… Publius Plotius Glycerus, elected in the very distinguished council by the ex-laucelarchoi, and initiated, according to the custom, to the mystery of this priesthood, having perfected himself in a complete and total manner, dedicated”.

The names of other faithful follow.

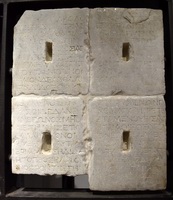

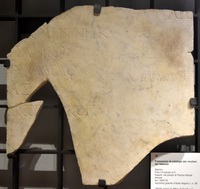

9 Lastra di marmo opistografa

Marmo

Napoli, fuori Porta Capuana.

Inv. 250166

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, II, n. 112 en. 153

Lato A - ricordo della sacerdotessa Domizia Calliste

Fine I secolo a.C. - inizio I d.C.

“Domizia Calliste sacerdotessa di Atena Sicula, divenuta (sacerdotessa) pubblica per volere del consiglio”.

Lato B - rilievo funerario I-II secolo d.C.

“O Paccio Eracleone”.

9 Opisthograph marble slab

Marble

Naples, outside Porta Capuana.

Inv. 250166

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, II, n. 112 e n. 153

Side A - commemoration of the priestess Domitia Calliste.

End of the 1st century BC - beginning of the 1st century AD.

“Domitia Calliste, priestess of Athena Sicula, who became public (priestess) by will of the council”.

Side B - funerary relief 1st-2nd century AD.

“O Paccius Heracleon”.

10 Dedica in onore di Publio Elio Antigenide

Marmo

Meta II secolo d.C.

Inv.2453

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 47

“Per decreto del consiglio la città di Napoli (onorò) Publio Elio Antigenide di Nicomedia e di Napoli, ex demarco, sommo sacerdote a vita delta sacra associazione teatrale degli artisti di Dioniso, primo e solo da che mondo è mondo ad aver vinto i sottoscritti concorsi, nei quali soli gareggiò invitto”. Dopo l’elenco delle gare vinte l’iscrizione si chiude nel modo seguente: “Si ritirò a 35 anni, dopo aver suonato il flauto per il popolo romano per 20 anni”.

10 Dedication in honor of Publius Aelius Antigenides

Marble

Middle of the 2nd century AD.

Naples, via S. Paolo.

Inv. 2453

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 47

“By decree of the council, the city of Naples (honoured) Publius Aelius Antigenides of Nicodemia and Naples, ex-demarchos, high priest for life of the sacred theatrical association of the artists of Dionysus, the first and only, from time immemorial, to win the contests listed below, in which he took part unbeaten”.

After listing the contests won by Antigenides, the inscriptions ends in the following manner: “He retired at 35, after having played the flute for the Roman people for 20 years”.

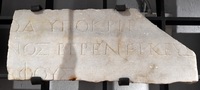

11 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

Fine I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli, nei pressi di Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250171

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 63

“(Vinse) gli attori di commedia (o tragedia) il tale di Berenice; gli autori di panegirici il tale”.

11 Fragment of a list of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

End of the 1st-2nd century AD.

Naples, near Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250171

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 63

“So-and-so from Berenice (won among) the comedy (or tragedy) actors; so-and-so (won among) the authors of panegyrics”.

12 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

178, 182 o 186 d.C.

Napoli, nei pressi di Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250167

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 54

“(Vinsero i Sebastà Italici Romani isolimpici nel concorso musicale: in una gara ignota il tale) dei cleruchi del distretto Ermontite dal villaggio di Gabai; nella gara di poesia lirica Graniano Fania (Artemidoro); nella gara fra tutti Lucio Aurelio Apolausto. Nel concorso ippico vinsero: col carro a due puledri Timandro figlio di Epercomeno; col puledro montato Settimio Ermofilo; col carro a due cavalli adulti Valerio Arpocrazione; col cavallo montato Felice Pro(…); col carro a quattro puledri Uf (…)”.

12 Fragment of a catalog of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

178, 182 or 186 AD.

Naples, near Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250167

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 54

“(These are the winners of the Italic Roman Iso-Olympic Sebastà in the musical competition: in an unknown contest so-and-so), of the cleruchs of the Hermontitis district, from the village of Gabai; in the lyric poetry contest, Granianus Phanias (Artemidorus); in the contest between all, Lucius Aurelius Apolaustus. These are the winners of the horse-racing competition: on the two-colt chariot, Timandrus, son of Eperchomenus; in colt-riding, Septimius Hermophilus; on the two adult horse chariot, Valerius Harpocration; in horse-riding, Felix Pro(…); on the four-colt chariot, Yph (…)”.

13 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

Fine I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli, nei pressi di Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250168

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 55

“(Sotto i consoli ?) Flacco (e … vinsero i Sebastà) Italici Romani (isolimpici), essendo demarco il tale, nel concorso ippico: col carro a due puledri Decimo Valerio; col puledro montato Tito Flavio Rufino; col carro a due puledri Valerio Paolino; col… cavalli adulti Paolino”.

13 Fragment of a catalog of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

End of the 1st-2nd century AD.

Naples, near Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250168

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 55

“(Under the consuls ?) Flaccus (and …, these are the winners of the Italic Roman (Iso-Olympic Sebastà), so-and-so being demarchos, in the horse-racing competition: on the two-colt chariot, Decimus Valerius; in colt-riding, Titus Flavius Rufius; on… adult horse… Paulinus”.

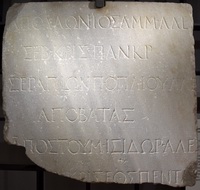

14 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

Fine I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli

Inv. 2457. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia.Napoli, I, n. 56

“Apollonio figlio di Ammonio di Alessandria (vinse) i pancraziasti della categoria augusta; Serapione figlio di Publio gli apobati; Aulo Postumio Isidoro i pentatleti della categoria augusta”.

Il pancrazio era un misto di lotta e pugilato, mentre l’apobates era una gara acrobatica.

14 Fragment of a catalog of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

End of the 1st-2nd century AD.

Naples

Inv. 2457. Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I, n. 56

“Apollonius son of Ammonius of Alexandria (won among) the pancratiastai in the augustan category; Serapion, son of Publius, the apobates; Aulus Postumius Isidorus the pentathlets in the augustan category”.

Pancratium was a combination of wrestling and boxing, while the apobates was an acrobatic contest.

15 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

Fine I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli, nei pressi di Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250169

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia. Napoli, I. n. 58

“Nella lotta il tale figlio di (…) omeno di Nicodemia (?); nel pancrazio il tale di Filadelfia; (vinse) i pugili il tale di Nicopoli”.

Sul lato destro della lapide si leggono le parole “undicesima parodos” la cui interpretazione è controversa.

15 Fragment of a list of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

End of the 1st-2nd century AD.

Naples, near Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250169

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 58

“In wrestling, so-and-so, son of (…) omenus of Nicodemia (?); in pancratium, so-and-so of Philadelphia; so-and-so from Nicopolis (won among) the boxers”.

On the right side of the stone are engraved the word “eleventh parodos”, the interpretation of which is controversial.

16 Frammento di catalogo dei vincitori dei Sebastà

Marmo

Fine I-II secolo d.C.

Napoli, nei pressi di Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250170

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 59

“(Nella corsa ?) Attico di Sardi; nel pentathlon il tale di Atene; nella lotta, categoria adulti, Lisimaco di Sparta; nel pugilato Alcimo, detto anche Miccalo, di Sardi”.

16 Fragment of a list of the winners of the Sebastà

Marble

End of the 1st-2nd century AD.

Naples, near Piazza Nicola Amore

Inv. 250170

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 59

“(In racing ?) Atticus of Sardis; in pentathlon so-and-so from Athens; in wrestling, in the adult category, Lysimachus of Sparta; in boxing, Alcimus, also called Miccalus, of Sardis”.

17 Base di marmo modanata

Lato A - dedica delta fratria degli Eumelidi a due fratelli vincitori in gare di corsa ai Sebasta. 170 d.C.

Lato B - offerta di doni ai Dioscuri da parte dei genitori dei due atleti. 171 d.C.

Napoli

Inv. 2455

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 52

Lato A. “Tito Flavio Euante figlio di Tito, che ha vinto nei Sebastà Italici Romani isolimpici della 43esima Italide la corsa del doppio stadio (riservata) ai fanciulli cittadini, e che ha dedicato nella fratria statue dei Dioscuri insieme al fratello Tito Flavio Zosimo, che nello stesso concorso ha vinto il tagma (?) ed ha riportato un premio, i fratri Eumelidi (dedicarono) per riconoscenza”.

Lato B. “Sotto i consoli Severo ed Erenniano, l’11 marzo, i genitori Tito Flavio Zosimo e Flavia Fortunata in ringraziamento di nuovo consacrarono ai Dioscuri candelabri con lucerne e altari”.

Nella corona: “Sebastà”.

17 Marble slab

Side A - dedication of the phratry of the Eumelidai to two brothers, winners of the races in the Sebastà 170 AD.

Side B - offering of gifts to the Dioscuri on the part of the parents of the two athletes. 171 AD.

Naples

Inv. 2455

Iscrizioni greche d’Italia Napoli, I, n. 52

Side A:“To Titus Flavius Euanthes son of Titus, who has won, in the Italic Roman Iso-olympic Sebastà of the 43th Italis, the double stadium race, (reserved) to the city youths, and who dedicated statues of the Dioscuri in the phratry with his brother Titus Flavius Zosimos who, in the same games, won the tagma (?) and gained a prize, the Eumelidai phretores (dedicated) in gratitude”.

Side B. “Under the consuls Severus and Erennianus, on March 11, the parents Titus Flavius Zosimos and Flavia Fortunata, in thankfulness again consecrated to the Dioscuri candelabra with lamps and altars”.

In the crown: “Sebastà”.

18 Stele

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Calcare

Fine IV, inizio III secolo a.C.

San Prisco (Caserta), fondo Patturelli (1894)

Inv. 250173 (Vetter 90 - Franchi De Bellis 13)

L’Iscrizione mutila non è immediatamente comprendibile. La consacrazione della iúvla è fissata per le feste pomperie nel mese di Mamertio. Nel terzo e nel quarto rigo, per motivi di spazio le parole proseguono con le ultime due lettere incise in senso perpendicolare al rigo.

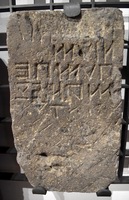

18 Stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

End of the 4th-beginning of the 3rd century BC.

San Prisco (Caserta), near the Patturelli estate (1894)

Inv. 250173 (Vetter 90 - Franchi De Bellis 13)

This mutilated inscription is not easily understandable. The consecration of the iúvila is scheduled for the pomperiae of the month of Mamertius. For lack of space, the two last letters of the third and fourth lines are engraved perpendicularly to the line.

19 Stele

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Tufo

III secolo a.C.

San Prisco (Caserta), fondo Patturelli (1889)

Inv. 119004 (Vetter 85 - Franchi De Bellis 22)

“(Questa e la iúvila di Spurio) Calovio e dei fratelli. Durante le ferie pomperie prima di Mamertio, nella magistratura di Lucio Pettio ebbero luogo i sacrifici cruenti”.

Il nome del personaggio, Spurio, è noto da un’altra stele che ricorda le kerssnasias di consacrazione della iúvila di Spurio Calovio e dei fratelli, mentre quella qui esposta ricorda le sakrasias. La consacrazione della iúvila è fissata per le pomperie del mese precedente quello di Mamertio.

La circonlocuzione si spiega forse con il divieto culturale di nominare il mese legato at culto dei morti.

19 Stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

3rd century BC.

San Prisco (Caserta), near the Patturelli estate (1889)

Inv. 119004 (Vetter 85 - Franchi De Bellis 22)

“(This is the iúvila of Spurius) Calovius and of his brothers. During the pomperial feriae before Mamertius, under the magistrateship of Lucius Pettius, the bloody sacrifices took place”.

The name of the person, Spurius, is known from another stele commemorating the kerssnasias for the consecration of the iúvila of Spurius Calovius and of his brothers, while the one on exhibition here commemorates the sakrasias. The consecration of the iúvila is scheduled for the pomperiae of the month preceding that of Mamertius. This circumlocution is perhaps due to a cultic interdiction to name the month connected to the cult of the dead.

20 Stele

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Tufo

Prima meta del III secolo a.C.

San Prisco (Caserta), fondo Patturelli (1889)

Inv. 119005 (Vetter 86 - Franchi De Bellis 20)

taeffúd (righi 8-9) è lettura di R. Antonini. A. Franchi De Bellis legge staieffud.

“Iúvilas di Opilio, Vibio, Pacio Tanternei da rendere sacre alle idi di Mamertio, quando sarà presente il meddís capuano durante le prossime giovie. …siano consacrate con porcelli (sarissa), ma l’ultima con cene (kerssnaís)”.

20 Stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

First half of the 3rd century BC.

Capua, near the Patturelli estate (1889)

Inv. 119005 (Vetter 86 - Franchi De Bellis 20)

taeffúd (lines 8-9) is the reading of R. Antonini. A. Franchi De Bellis reads staieffud.

“Iúvilas of Opilius, Vibius, Pacius Tanternei, to be made sacred on the ides of Mamertius, when the Capuan meddís will be present during the next Jovians. …let them be consecrated with piglets (sakriss), but the last ones with banquets (kerssnaís)”.

21 Stele

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Tufo

Prima meta del III secolo a.C.

San Prisco (Caserta), fondo Patturelli (1889)

Inv. 119006 (Vetter 87 - Franchi De Bellis 21)

“Iúvila di Opilio, Vibio, Pacio Tanternei da rendere sacra durante le pomperie solenni, quando sarà presente un magistrato o un rappresentante della verehia … sia consacrata con un porcello (sakrid)”.

Idi e pomperie sono feste mensili; nelle idi si celebravano le giovie, feste in onore di Giove. Mamertio (= di Marte) e il primo mese dell’anno osco. Sakri- è il sacrificio cruento, probabilmente di un porcellino; kerssna è interpretato come cena rituale a base di cereali. La verehia doveva essere un’importante istituzione cittadina, se un suo rappresentante poteva garantire la legalità dei riti allo stesso titolo di un magistrato.

21 Stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

First half of the 3rd century BC.

San Prisco (Caserta), near the Patturelli estate (1889).

Inv. 119006 (Vetter 87 - Franchi De Bellis 21)

“Iúvila of Opilius, Vibius, Pacius Tanternei, to be made sacred during the solemn pomperiae, when a magistrate or a representative of the verehia will be present… let it be consecrated with a piglet (sakrid)”.

Ides and pomperiae were monthly celebrations. During the ides, the Jovians were celebrated. The latter were ceremonies in honor of Jupiter. Mamertius (i.e. “of Mars”) is the first month of the Oscan year. Sakri- is the bloody sacrifice, probably of a piglet; kerssna is thought to indicate a ritual meal based on cereals. The verehia must have been an important city institution, if one of its representatives could guarantee the legitimacy of rituals on the same standing as a magistrate.

22 Iscrizione sepolcrale

Scrittura da destra a sinistra

Intonaco

Fine IV a.C.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta)

Inv. 111972 (Vetter 96)

“Offello Salvio (figlio di) Minio”.

22 Sepulchral inscription

Written from right to left

Painted on plaster

End of the 4th century BC.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta)

Inv. 111972 (Vetter 96)

“Offellus Salvius (son of) Minius”.

23 Iscrizione sepolcrale

Scrittura da destra a sinistra

Intonaco

III secolo a.C.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta)

Inv. 111971 (Vetter 95)

“Offello padre di Minio oppure Offello, padre, figlio di Minio”.

Le iscrizioni provengono da un sepolcro familiare. Mentre il secondo personaggio è ricordato con la formula onomastica completa proprio-gentilizio-paternità, il primo, caso molto raro, ha la definizione “padre” al posto del gentilizio; forse si voleva sottolineare con forza il ruolo di pater familias del personaggio. In questa iscrizione la parola miÍnieis presenta due caratteristiche dell’osco più recente (III secolo a.C.): il segno, traslitterato con -Í-, che indicava un suono intermedio tra i ed e (presente, del resto in diverse iúvilas) è la desinenza del genitivo in -eis. L’iscrizione di Offello Salvio, che non presenta queste caratteristiche, risalirà alla fine del IV secolo a.C.

23 Sepulchral inscription

Written from right to left

Painted on plaster

3rd century BC.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta)

Inv. 111971 (Vetter 95)

“Offellus father of Minius father, son of Minius”.

These inscriptions come from a family tomb. While the second person is commemorated with the complete onomastic formula (personal name-family name-father’s name), the first, an exceptional case, has the definition “father” instead of the family name. Possibly this is due to an intention to stress the person’s role as parter familias, in this inscription, the word miÍnieis has two characteristics of late Oscan (3rd century BC): the sign, transliterated as - Í -, which represented an intermediate sound between i and e (found in several iúvilas), and the desinence of the genitive in -ies. This inscription of Offellus Salvius, which does not present these characteristics, is probably dated to the end of the 4th century BC.

24 Terracotta opistografa, effigiata, nella faccia a, da una testa femminile in bassorilievo; nella faccia b da un porcellino

Scrittura da destra a sinistra

Terracotta

IV secolo a.C.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta), la provenienza dal fondo Patturelli è incerta

Inv. 2534 (Vetter 76 - Franchi De Bellis 6)

“Dei Clovati. Alle giovie. Con pubblici banchetti”

L’iscrizione ricorre sui due lati. La iúvila è detta appartenente ai Clovati, senza specificazione di membri della famiglia. Quest’uso del gentilizio ricorre in genere nelle iscrizioni più arcaiche. La testa della divinità impressa sulla terracotta, forse Minerva, indica il mese. Il porcellino in rilievo allude al sacrificio cruento, consumato in banchetti pubblici (damusennias). Il termine damusennias deriverebbe dal greco damathoinía, e attesterebbe la diffusione in ambito italico, di un’usanza greca irradiata da Taranto.

24 Opisthograph terracotta representing, on face a, a female head in bas-relief, on face b, a piglet

Written from right to left

Terracotta

4th century BC.

Santa Maria Capua Vetere (Caserta), its origin from the Patturelli plot is not totally certain.

Inv. 2534 (Vetter 76 - Franchi De Bellis 6)

“Of the Clovati. To the Jovians. With public banquets”.

The inscription is repeated on both faces. The iúvila is said to belong to the Clovati, without specifying to which members of the family. This use of the family name is generally found in the more archaic inscriptions. The head of the deity impressed on the terracotta, possibly Minerva, indicates the month. The piglet in relief is an allusion to the bloody sacrifice, which was consumed during public banquets (damusennias). The term damusennias is thought to derive from the Greek damothoinía, and to attest the diffusion in the Italic world of a Greek custom that spread from Tarentum.

25 Sostegno di labrum

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Marmo

II secolo a.C.

Cuma, nelle cd. Terme centrali

Inv. 183127 (Pocetti 134)

“Ma(raio) Heio (figlio di) Decio, meddix della vereia e il meddix X [oppure: “e i meddices X”], questa fliteam comprarono”.

Il supporto di vasca col suo piedistallo era collocato entro un bacino quadrato inserito nel pavimento. Il termine fliteam che designa l’oggetto acquistato, non è traducibile con certezza. Si pensa fosse un dono per il gymnasium (palestra) sede della vereia.

25 Support for a basin

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Marble

2nd century BC.

Cumae, found in the Central Thermae

Inv. 183127 (Pocetti 134)

This support for a basin stood on a pedestal within a square basin inserted in the floor.

The term fliteam, which refers to the purchased object, is not translatable with certainty. It is thought to have been a gift for the gymnasium where the vereia had its seat.

26 Mattone con bollo rettangolare

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Terracotta

Fine III - II secolo a.C.

Cuma

Inv. 230782 (Poccetti 130)

Il bollo attesta la proprietà di una fabbrica di manufatti d’argilla da parte degli Heii, una delle famiglie più in vista a Cuma tra il III e il I sec. a.C., che partecipa ai lavori del grande tempio sannita della città bassa.

26 Brick with rectangular stamp

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Terracotta

End of the 3rd - 2nd century BC.

Cumae

Inv. 230782 (Poccetti 130)

The stamp attests the ownership of a workshop producing clay artefacts on the part of the Heii, one of the most eminent Cumaean families between the 3rd and 1st century BC, who took part in the building of the great Samnite temple of the lower city.

27 Elemento del piedistallo della statua di culto; presenta sulla faccia superiore dei fori dovuti a reimpiego. Sulla faccia opposta si trova un’iscrizione latina illeggibile pure dovuta a reimpiego della pietra

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra a sinistra

Calcare

II secolo a.C.

Cuma

Inv. 250172 (Vetter 108 - Poccetti 132)

“[Dedicante di cui si è perso il nome] (figlio di)…, meddix della vereia e il meddix X [oppure: “e i meddices X”], questo … a Giove Flagio a nome della vereia in dono diedero”. Il nome dell’oggetto donato è restituibile con sufficiente credibilità; in si [--]únúm infatti potrebbe riconoscersi il termine osco per “statua”, corrispondente al latino signum. Rinvenuta nella muratura di un pilastro nell’area del tempio di Apollo sull’acropoli, l’epigrafe potrebbe provenire dal grande tempio della città bassa, che si ritiene appunto dedicato a Giove.

27 Part of the pedestal of a cult statue. The holes on its upper face indicate that it was reemployed. On the opposite face there is an unreadable Latin inscription, also engraved when the stone was re-employed

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Limestone

2nd century BC.

Cumae

Inv. 250172 (Vetter 108 - Poccetti 132)

“[Dedicator whose name is lost] (son of)…, meddix of the verehia and the meddix X [or: “and meddices X”], gave this as a gift …to Jupiter Flagius in the name of the verehia”. The name of the donated object can be restored with sufficient plausibility: si[..]únúm could be interpreted as the Oscan term for “statue”, corresponding to the Latin signum. This epigraph, found in the walling of a pillar in the area of the temple of Apollo, on the acropolis, may originally have stood in the great temple of the lower city, which was probably dedicated to Jupiter.

28 Frammento di stele conformata ad edicola

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Tufo

II secolo a.C.

Cuma

Inv. 2537 (Vetter 110)

L’iscrizione sepolcrale consta della formula di saluto al defunto: “stai bene, o Stazio Silio”.

28 Fragment of an aedicule-shaped stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

2nd century BC.

Cumae

Inv. 2537 (Vetter 110)

This sepulchral inscription consists of the greeting formula to the deceased: “Be well, oh Statius Silius”.

29 Frammento di stele

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Tufo

II secolo a.C.

Cuma

Inv. 2538 (Vetter 111)

“Caio Sillio (figlio di) Caio”.

29 Fragment of a stele

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

2nd century BC.

Cumae

Inv. 2538 (Vetter 111)

“Caius Sillius (son of) Caius”.

30 Stele con la rappresentazione di un flabello, di una cassettina contenente un porta unguenti ed uno specchio

Alfabeto osco, scrittura da destra verso sinistra

Tufo

II secolo a.C.

Cuma

Inv. 115388 (Vetter109)

Gli oggetti rappresentati indicano che la stele è pertinente ad una sepoltura femminile.

L’iscrizione mutila, formula un augurio per la defunta: “le ossa della sepolta vanno in terra, la sua anima in cielo”.

30 Stele. On it are represented in bas-relief a flabellum and a small box containing an ointment-holder and a mirror

Oscan alphabet, written from right to left

Tuff

2nd century BC.

Cumae

Inv. 115388 (Vetter 109)

The depicted objects indicate that the stele originally belonged to a female burial. The mutilated inscription contains a well-wishing formula for the deceased: “the bones of the buried one go into the earth, the soul up into the sky”.

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis