Indice dei Musei

presenti in miti3000

Napoli Museo Nazionale - Piano - 1 - Sezione Epigrafi

Testo

MANN - Piano meno uno - Sezione Epigrafi

Sala CLIII

Clicca sulle immagini per vedere l'ingrandimento, sulle scritte evidenziate per altre informazioni.

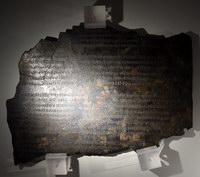

IL PROCESSO DI ROMANIZZAZIONE

Dalla seconda metà del IV sec. a.C., con le guerre sannitiche, ebbe inizio il processo di espansione che portò Roma alla conquista della egemonia in Italia e nel Mediterraneo, un processo che ebbe come conseguenza la progressiva romanizzazione - cioè l’integrazione nella realtà unitaria dell’impero - delle comunità e dei popoli alleati e sottoposti. Roma utilizzò vari mezzi per esercitare l’egemonia: l’incorporazione nel proprio territorio di altre città (municipia), la fondazione di colonie, la concessione della cittadinanza senza diritto di voto (civitas sine suffragio), trattati bilaterali (foedera). Le comunità dell’impero erano, per lo più, subordinate a Roma in politica estera ed erano tenute a fornirle contingenti militari; tuttavia godevano di una certa autonomia negli affari interni. Nonostante le ingerenze di Roma nella vita delle comunità soprattutto dal II sec. a.C., la romanizzazione fu anche un fenomeno spontaneo, perché le comunità erano in buona misura compartecipi dei benefici derivanti dall’egemonia di Roma nel Mediterraneo, e soprattutto le élites locali desideravano prendere parte alla gestione dell’impero. La romanizzazione fu un fenomeno estremamente complesso ed estremamente diversificato nei suoi esiti locali. I testi esposti in questa sala, provenienti dall’Italia meridionale e da Roma, ne danno solo uno spaccato, per quanto significativo. Sono segni di romanizzazione la diffusione della lingua latina, l’uniformità dello schema delle magistrature cittadine e degli statuti municipali nelle realtà locali (nn. 1, 5-6) l’adozione da parte loro delle leggi e del diritto romani; ma anche le leggi con cui Roma regolava la procedura penale (nn. 3, 5), il regime delle terre demaniali (n. 3), i rapporti con singole comunità (n. 4), o cercava di rendere più efficiente l’amministrazione dell’impero (n. 2).

The process of Romanization

From the Samnite wars on (second half of the 4th century BC), Rome went through a great process of expansion, gaining military, political and economic hegemony over the rest of Italy and in the Mediterranean. This process resulted in a gradual Romanization - i.e. integration into the Empire - of the allied or subject populations. To exercise its hegemony, Rome availed itself of various means, such as the incorporation into its territory of other cities (municipia), the foundation of colonies, the concession of citizenship without the right to vote (civitas sine suffragio) and the concluding of bilateral treaties (foedera). The allied communities were, for the most part, subjected to Rome in their foreign policy, and were under the obligation to provide it with troops. They enjoyed, however, a certain degree of autonomy in their internal affairs. Although, especially from the 2nd century BC, the government of Rome often interfered heavily into the life of the individual communities, Romanization also took the form of a spontaneous phenomenon, because the allies looked up to the Roman model, benefited from Rome’s hegemony in the Mediterranean and, above all, their local elites wished to take part in the management of the Empire. The Romanization of Italy was by then essentially accomplished on the juridical plane. The epigraphic texts on exhibits in this room, most of which are from southern Italy, illustrate the different ways in which Rome managed its empire in the Republican age. They include judicial laws and municipal statutes (nos. 1, 5-6) and others illustrating the internal management of public administration in “Romanized” communities (nos. 3, 5) or providing examples of how Rome managed its relations with its overseas allies (no.3). The remaining epigraphs on exhibit also concern important aspects of the social life of Roman Italy.

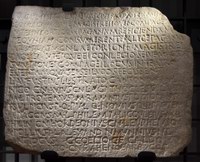

Le città romane dell’Italia meridionale

Prima della guerra sociale (91-89 a.C.) le città dell’Italia antica avevano, in relazione a Roma, diverse condizioni giuridiche. Alcune rientravano nell’ager manus e godevano della cittadinanza romana, come i municipia. - città preesistenti alla loro incorporazione nello stato romano- e le coloniae civium Romanorum: presidi militari composti da un piccolo nucleo di cittadini di pieno diritto (in genere 300) inviati da Roma. Altre città erano stati formalmente indipendenti, come le colonie di diritto latino (coloniae Latinae) e le civitates foederatae, legate a Roma da un trattato. Queste ultime potevano avere varia origine etnica (greca, etrusca, osca, etc.). Le città erano il perno della romanizzazione e dell’organizzazione amministrativa romana, ma in alcune regioni della penisola il fenomeno urbano era poco diffuso ed il territorio era strutturato in distretti territoriali (pagi) al cui interno sorgevano piccoli nuclei abitativi (vici). Dopo la guerra sociale e la concessione della cittadinanza romana alle popolazioni della penisola, bisognò riorganizzare le strutture amministrative delle comunità locali per consentire un’adeguata partecipazione alla vita politica dello stato romano. Si ebbe così l’estensione dell’istituto del municipium alle colonie latine e agli alleati. Lo schema dell’ordinamento municipale era uniforme: i quattuorviri erano i magistrati supremi con poteri giurisdizionali, c’era poi il consiglio degli ex magistrati (i decurioni), e l’assemblea popolare. Gli statuti municipali (nn. 1, 5-6) derivavano da un archetipo comune, adattabile alle esigenze locali.

The Roman Cities of Southern Italy

Before the Social War (91-89 BC), the relations between the cities of ancient Italy and Rome were regulated by different juridical status. Some cities were part of the ager Romanus and enjoyed Roman citizenship, e.g. the municipia - townships pre-existing their incorporation into the Roman state - and the colonies of Roman citizens (coloniae civium Romanorum). Others were formally independent states, e.g. the colonies ot Latin law (coloniae Latinae) and the civitates foederatae - i.e. bound to Rome by a treaty - which had different ethnic origins (Greek, Etruscan, Oscan etc.). The cities were the core of the process of Romanization and of the Roman administrative organization. In some regions of the peninsula, however, urbanization was scarce, and their territories were hence divided into territorial districts (pagi) in which there were small settlements called vici. After the Social War and the concession of Roman citizenship to all the populations of the peninsula, it was necessary to reorganize the administrative structures of the local communities to grant them an adequate participation in the political life of the Roman state. The statute of municipium was thus extended to the Latin colonies and to the allies. The pattern of the municipal organization was uniform: it was made up of the quattuorviri, the supreme magistrates, with jurisdictional powers, the council of former magistrates (the decurions), and the popular assembly. Municipal statutes (nos. 1, 5-6) were based on a common archetype, for reasons of uniformity, but could be adjusted to local necessities.

La Misurazione della terra

Nel 133 a.C. il tribuno della plebe Tiberio Gracco per far fronte all’occupazione abusiva e alla concentrazione in poche mani dell’ager publicus (i terreni demaniali), presentò una proposta di riforma agraria. Essa prevedeva di limitare il possesso di ager publicus per ogni individuo a 500 iugeri (125 ettari), più 250 iugeri per ciascun figlio fino a un massimo di 1000 iugeri. All’occupante era garantito il possesso perpetuo di tali quote. I terreni eccedenti ritornavano allo Stato e una commissione di tre membri (Triumviri Agris Dandis Adsignandis) provvedeva a redistribuirli ai nullatenenti in lotti inalienabili. Osteggiata dagli occupanti abusivi delle terre demaniali, la commissione incontrò numerose difficoltà, tra cui, stabilire, in assenza di mappe catastali aggiornate, lo stato giuridico privato o pubblico dei terreni. Una nuova legge le diede, quindi, anche potere giudicante (Triumviri Agris Dandis Iudicandis Adsignandis) e fu avviata una vasta opera di misurazioni catastali che affiancò il recupero dell’agro pubblico e la distribuzione dei lotti.

The land measuring

In 133 BC, Tiberius Gracchus, tribune of the plebs for that year, presented a bill proposing an agrarian reform limiting possession of public land on the part of privates to 500 iugeri (125 hectares), a quota that could be increased by 250 iugeri for each child up to a maximum of 1000 iugeri. Permanent possession of these quotas would be guaranteed to the owner. The surplus land would be incorporated by the State. A triumviral commission Triumviri Agris Dandis Adsignandis), was entrusted with the task of delimiting inalienable plots intended for persons without property. The triumviri were confronted with many obstacles: it was difficult, in absence of updated cadastral maps, to establish if a given plot of land was public or private, and to settle disputes with the Italic allies, whose territories were also involved in the program; furthermore, they had to face the hostility of the rich landowners who had monopolized the use of public land. To cope with all these problems, a new law was passed giving them judicial powers as well (the commission was hence renamed Triumviri Agris Dandis Iudicandis Adsignandis). A large scale operation of cadastral measurement was thus set up, public land was recuperated and the plots were redistributed. A series of “gromatic” (i.e. land-meansuring) cippi found in the Picenum and in Campania, Samnium and Lucania, including the cippus of Atena Lucana (n. 7), document the activities of this agrarian commission in these regions, i.e. the measuring and delimiting of private from public land. Centuriatio was the basic operation: the division of land into a regular grid of horizontal (decumani) and vertical (kardines) axes traced on the ground with a groma.

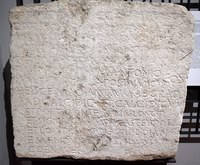

I Calendari

Il calendario arcaico comprendeva dodici mesi per 355 giorni. Era lunisolare: il succedersi dei mesi era basato sulle lunazioni, ma si colmava ogni due anni la differenza sulla rivoluzione terrestre con un mese intercalare di 22 o 23 giorni. La differenza era dunque colmata per eccesso, per cui talvolta era omessa l’intercalazione. Il compito di registrare le lunazioni e di ordinare le intercalazioni spettava ai pontefici, massima autorità religiosa romana. Il nostro calendario discende dalle riforme di Giulio Cesare (46 a.C.) e di papa Gregorio XIII (1582), fondate sul calcolo astronomico del periodo di rivoluzione terrestre. Il mese romano era diviso in tre parti: calende (abbreviate con Kal o K), none (Non), idi (Eid) che originariamente indicavano tre momenti della lunazione. La funzione delle nostre settimane era svolta dalle nundinae (“nove giorni”). Esse comprendevano in realtà otto giorni, e il loro nome si spiega col conteggio romano che includeva anche il primo giorno della serie successiva. I giorni erano contrassegnati dalle prime otto lettere dell’alfabeto (A-H), dette nundinali. All’inizio di ogni serie si teneva il mercato. Le nundinae saranno sostituite dalla settimana a partire dal I sec. d.C.

I fasti sono i calendari che contengono tutti i giorni dell’anno (nn. 15, 16). I feriali annotano soltanto le feste (n. 18). I Menologi forniscono per ogni mese il numero dei giorni, la loro suddivisione, la lunghezza del giorno e della notte, il segno zodiacale, il nume tutelare, le operazioni agricole, le feste ed i riti più importanti (n. 14). Gli Indices nundinarii sono liste di città con l’indicazione dei giorni in cui vi si svolgevano le nundinae, mercati cittadini che si tenevano ogni otto giorni (n. 17).

Calendars

The archaic calendar comprised 355 days divided into twelve months. It was lunisolar, that is, the succession of months was based on the revolutions of the moon; however, every two years the difference with the solar year was compensated by intercalating a leap-month of 22 or 23 days. The difference was thus actually overcompensated, which is why the intercalation was sometimes omitted. The task of recording moon revolutions and ordering intercalations fell to the pontifices, the highest Roman religious authority. Our own calendar derives from the reforms of Julius Caesar (46 BC) and pope Gregorius XIII (1582), founded on astronomical calculations of the duration of the Earths revolution. The Roman month was divided into three parts: Kalends (abbreviated as Kal or K), Nones (Non), and Ides (Eid). These names originally designated moon phases. The function of our weeks was performed by nundinae. The word means “ninth day”, but they actually comprised only eight days. This is due to the Roman counting system, which also included the day one counted from. The days were designated by the first eight letters of the alphabet (A-H), hence called “nundinal letters”. Markets were held at the beginning of each nundinal cycle. Nundinae were replaced by weeks in the first century AD. Fasti are calendars listing all the days of the year (nos. 15, 16). Ferialia only indicate holidays (no. 18). Menologia give the number of days of each month, their subdivision, the length of day and night, the sign of the zodiac, the tutelary deity, agricultural tasks, and the principal holidays and rites (no. 14). Indices nundinarii are lists of towns with indications of the days when nundinae were held in each. Nundinae were town markets held every eight days (no. 17).

Spazio e tempo

L’ORGANIZZAZIONE E IL CONTROLLO DELLO SPAZIO

L’organizzazione del territorio, nella mentalità romana, deve proiettare nello spazio un duplice ordine: politico-amministrativo, stabilendo la condizione giuridica di ogni porzione di territorio; divino, riproducendo sulla terra l’ordine cosmico, attirando così sulla comunità il consenso degli dei, garanzia di prosperità comune. I cippi di confine erano infissi nel terreno per segnalare la natura e i limiti delle proprietà private e pubbliche nonché delle circoscrizioni territoriali amministrative. L’estrema importanza rivestita da queste operazioni è rivelata dal complesso rituale che presiede alla collocazione dei cippi (nn. 7, 8, 10), dall’importanza del culto di Terminus (confine; pietra di confine), dalla legge del re Numa che dichiarava sacer (sacrilego) chiunque avesse scalzato un segno di confine.

L’ORGANIZZAZIONE E IL CONTROLLO DEL TEMPO

I Romani regolavano accuratamente la scansione del tempo umano, qualificando con precisione i giorni dal doppio punto di vista dell’attività umana e del culto degli dei. La qualità dei giorni era indicati da sigle:

F =fastus, i giorni in cui era lecito amministrare la giustizia. Il termine fasti indica, per estensione, il calendario stesso.

N = nefastus, i giorni in cui non si poteva amministrare la giustizia, inadatti a qualsiasi attività.

NP = contraddistingue quasi tutte le feste pubbliche, ma non ci è stato tramandato il significato. Sono giorni nefasti, ma evidentemente di una qualità speciale. Potrebbe trattarsi di giorni in cui si celebravano i riti espiatori (nefaspiaculum).

C = comitialis, giorni fasti in cui si potevano tenere le assemblee.

EN = endotercisus, giorni (sette in tutto) divisi in tre parti, nefasti nella prima e nella terza parte, fasti in quella mediana. Esistono poi giorni religiosi, in cui è vietata qualsiasi attività cultuale e civile. I giorni festivi per eccellenza sono le feriae. Nel calendario arcaico, precedente la riforma di Giulio Cesare del 46 a.C., esse erano 120 su 355 giorni. Dei 235 giorni fasti, solo 92 erano comitiales, cioè dedicati all’attività politica. Essi aumentarono gradualmente, per il primato riconosciuto agli affari pubblici.

Space and time

the organization and control of space

Territorial organization, as the Romans conceived it, was a spatial projection of political activity, and was a way to manifest the consensus of the gods, indispensable to public prosperity. The roads and border cippi made tangible, and somehow permanent, the collective image of the appropriation and valorization of land. The border cippi were erected to delimit and indicate public and private property, as well as administrative territorial districts. The extreme importance originally attributed to these operations is borne out by the elaborate ritual followed in the erection of the cippi (nos. 7, 8,10), the importance of the cult of Terminus and Numas law branding as sacer whoever removed a boundary stone. The cippi placed to delimit the ager publicus according to the Gracchan laws are of great historical interest. Some examples are on exhibit on the other side of the room.

the organization and control of time

The Romans accurately fixed the subdivisions of time regulating the activities of the city. They classified the days from the double point of view of human activity and the cult of the gods. The acronyms indicating the characteristics of the days are the following:

F: faustus: on fasti days it was licit to administer justice. The ter fasti eventually was used to indicate the calendar itself.

N: nefastus: on these days, one could not administer justice or engage in any other kind of activity.

NP: the meaning of this acronym is not known. It is used for nearly all public festivals. On these days, all profane activities were suspended and they were therefore nefasti, but obviously special.

C: comitialis, the fasti days on which it was licit to hold the comitia.

EN: (endotercisus), days divided into, three parts, nefasti in the first and third part, fasti in the middle one (there were seven of them in all).

There also existed a certain number of days qualified as “religious”, on which any profane, religious or public activity was interdected.

The festive days par excellence were the feriae. In the pre-Julian calendar there were 120 of them, out of 355 days. They generally occurred on odd days, so as to avoid the taking place consecutively. Of their the approximately 235 days indicated as fasti, only 92, called comitial days, were devoted to political activity. These were gradually increased on account of the growing importance attributed to political affairs.

Fotografie di Giorgio Manusakis